| ORGANISE!

for revolutionary anarchism

Cover price £2.00 (Free to Prisoners) - postage extra. |

|

| ORGANISE!

for revolutionary anarchism

Cover price £2.00 (Free to Prisoners) - postage extra. |

|

CONTENTS - ORGANISE! for revolutionary anarchism no. 73, Magazine of the Anarchist Federation

Magazine now available to download or read free online in PDF format, although please consider donating to our press fund.

To order a printed copy see Organise! main page or online from Organise! paypal page.

For links to all Anarchist Federation publications, visit http://www.afed.org.uk

ARTICLES - Winter 2009 - FULL CONTENTS Organise! magazine Issue 73 Winter 2009:

EDITORIAL – WHAT’S IN THE LATEST ORGANISE!

Admittedly the ‘moneygeddon’ topic has been done to death. The authoritarian left have very noticeably been cashing in on it for the last six months. But while it may be a bit passé nowadays to talk about the recession, the realities of capitalism’s failures continue to be felt widely by the working class. Since the G20 the neo-liberalist agenda has had to redefine itself, something which is explored in the article ‘G20 and New Capitalism’. In the face of the economic downturn working class people and students across the country have taken up occupation as a tactic against attacks on their jobs and conditions. We explore the history of the occupations movement and discover the importance of that tradition. We take a look at the situation in China, exposing the conflicts between the Chinese working class and the ruling Communist Party and discuss how the policing tactics during the G20 have changed in the face of state fears.

We also have an AF member’s view of the anarchist conference back in June and take a look at the history and continuing influence of the surrealist movement.

And

as with every issue, if you have any comments, suggestions or

complaints please email the editors at: organise@afed.org.uk

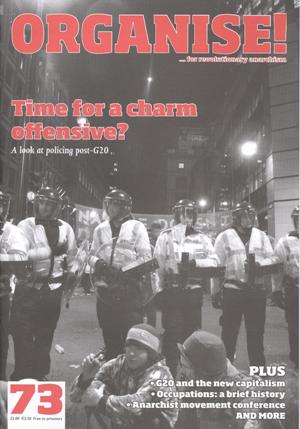

TIME FOR A CHARM OFFENSIVE? A look at British policing post-G20

“We have to win back the public’s trust.” Those were the words of outgoing Metropolitan Police chief Sir Ian Blair at a public lecture in November 2008, just days before his retirement. It was the killing of an innocent Brazilian man, Jean Charles de Menezes, by a Metropolitan Police officer, and the enquiry that followed, that had eventually led to his departure. Fast forward almost half a year and the Met have the death of another innocent man on their hands. This time it’s newspaper vendor Ian Tomlinson, who while walking home from work is inadvertently caught in the anti-G20 protests and struck heavily from behind by an officer in riot gear. Just as in the de Menezes case, controversy would surround the tragedy. Tomlinson’s body would be kept from his family for six days following his death, a rushed first autopsy would find no suspicious grounds for his death, and only after video footage from a passer-by’s phone was leaked to the media would the perpetrators, and the true severity of the attack, be revealed.

April 1st 2009 was not a good day for the Metropolitan Police. Actually, scratch that. It would be better to say that April 3rd was a bad day for the Metropolitan Police. After all, until the video footage and photographs from the public slowly began to be picked up by the mainstream media, following the unfolding of the Tomlinson story, the news agencies had been generally supportive of the police. It was the media, after all, who had manufactured the frenzy around the G20 protests in the first place, the origins of which can be found in the now infamous remark by Superintendent David Hartshorn to the Guardian newspaper in February that Britain was headed for a “summer of rage”. Sky News had for days leading up to the event been reporting on the prospect of anarchist hordes “storming the city”, while widely publicising the advice from “officials” in the City of London to financial workers to dress down and avoid confrontation with protesters. The Daily Mail, for its part, had sent an undercover reporter into the “anarchist mob” and found shaven-headed “angry men” in the Whitechapel Anarchist Group keen to orchestrate the most heinous acts in the name of chaos and destruction. The clashes between protesters and police lines, and the small amount of property damage committed against the RBS building on the day, were all but a self-fulfilling prophecy as far as the mainstream media was concerned. As early as the afternoon of April 1st, the front page of The Evening Standard had already proclaimed that “riot police battle anarchy in the city”.

“Community-style policing”

The storm that followed the Tomlinson case, and with it the widespread criticism of the “kettling” tactic, has, for the time being at least, put the police under greater media scrutiny, especially in relation to the policing of public protest. (Of course one can only speculate as to the influence on the importance and longevity of this particular story of professional journalists’ experience of being “kettled” alongside protesters on April 1st.) “Community-style policing” is the establishment’s chosen weapon in its PR campaign to win back the public trust it has lost as a result of the G20 fallout. The strategy is simple – project a romanticised image of the neighbourhood bobby-on-the-beat, while playing up both the general public’s fear of low-level crime and the police’s effectiveness in tackling it.

Many constabularies across the country, including the Metropolitan Police, have signed a “policing pledge”. This pledge reaffirms the openness of the police force, its accountability and responsiveness to its “service users”, i.e. law-abiding citizens, and its willingness to open a dialogue with local communities. Local consultations are used to build up trust and present the image of a caring and responsive service; clear public targets are set; and if the service is “unsatisfactory” the constabulary is committed to resolving your “concerns”. It’s classic, neo-liberal public reform, already widely applied to health and education, extended to the provision of law and order. It essentially provides the illusion of power and responsibility as “consumption” of a “public service”, masking the real role of these institutions in undermining our power and denying us any responsibility over our communities. Fear also has an important part to play. “Anti-social” behaviour is a consistent concern for local communities, especially with regards to large groups of youths. The state, of course, is always keen to emphasise the positive impact that community policing, i.e. bobbies walking up and down your street, can have on this. They are happy to indulge popular fears inflated by the daily scaremongering of right-wing tabloids, as visible policing is argued to provide greater safety and protection – neither of which, of course, the police actually provide.

These basic principles have also been extended to the policing of public protest. At the Camp for Climate Action in Blackheath in August this year, senior officers told representatives from the camp that they would also be met with “community-style policing”. The Met even set up its own Twitter account, named CO11 Met Police after its public order unit codename, to provide information and advice to campers. Chief Superintendent Helen Ball said neighbourhood-style tactics, including a “low-key” presence, limited surveillance of activists and almost no use of stop-and-search powers, proved the Met had changed its approach since the G20 protests in April. She went on to clarify that the approach was “not an accident”, but was designed to build trust with activists after the G20, and would be repeated at future demonstrations.

So what is “community-style policing”?

Surveillance is absolutely key to understanding the police’s current strategy. While tactics such as “kettling” and the increasingly draconian use of stop-and-search powers came under media scrutiny after G20, the police’s use of evidence gathering teams and surveillance throughout the protests did not. Likewise, while the physical presence of police officers may have been limited during the Climate Camp, arguably the “test case” when it comes to the Met’s new strategy, this did not stop them using constant CCTV surveillance on the site or even infiltration by plain-clothed officers. Following the G20 protests, in an interview with Channel 4 News, a former chief of the Metropolitan Police argued against the increasing use of stop-and-search powers and in favour of low-level surveillance and the prosecution of activists on conspiracy charges. This is a tactic that seems to be being more widely applied. April 13th of this year saw the biggest pre-emptive raid on environmental campaigners in UK history, with 114 people arrested on suspicion of “conspiracy to commit trespass and aggravated criminal damage”. In January animal rights campaigners were sentenced to 11 years in prison for “conspiracy to blackmail” in their campaign to shut down the animal testing laboratory Huntingdon Life Sciences. This is all made far easier for the police by the fact that Britain also happens to be one of the most watched nations in Europe. There are up to 4.2m CCTV cameras in Britain - about one for every 14 people. The police also have one of the largest DNA database in the world. Emails, text messages and phone conversations are now stored and kept for monitoring, and local authorities have widely used anti-terror legislation to spy on local tenants.

What’s driving the new friendly face of the police is not any real overhaul of tactics, but merely a more strategic application of their powers. The mistake they made at G20 was to subject everyone, including a Liberal Democrat politician and members of the professional media, to their intimidation and violence. The truth is that they are still widely employing these measures; they are just applying them with greater prejudice. On a local level, no-one is bearing the brunt of this more than British youth. February’s Operation Staysafe weekend, for example, saw police “engage” 1,251 young people. “Engaged” means that they were stopped and spoken to but not found to be committing any crime or in any danger, meaning that they were stopped because... well, they’re young, so that means they must’ve been up to something dodgy, right? Recent figures obtained through the Freedom of Information Act have also revealed that West Mercia Police (the force that covers Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Shropshire) has captured and stored the DNA profiles of over 19,000 teenagers in the region. These profiles are being kept whether the youngsters have committed a crime or not.

How long the police plan to keep up this activity is unclear. It’s pretty clear that surveillance is here to stay as a mainstay of British policing. As far as protest is concerned, as media interest drops off it is equally likely that the police will quickly revert to the heavy-handed tactics of old. Of course it is also foreseeable that “community-style policing” may become part of a wider trend in relation to political protest. The more radical elements inside protest movements could easily become isolated as more liberal elements become willing to embrace the “faciltative” role of the police in minimally disruptive political protest - making it much easier for the police to come down hard on protesters that are deemed to be “crossing the line”. The reasonableness of the police towards peaceful elements of the protest movement helps win back public trust, while any meaningful, disruptive behaviour can be demonised through the eyes of the media.

Policing a crisis: the other story

There is always another story. For while the police may be now displaying some (temporary) magnanimity towards members of the direct action movement, when it comes to the very real threat of widespread working-class discontent about the economic recession they aren’t pulling any punches. When workers at the Vestas plant in Newport on the Isle of Wight occupied the top floor of offices in their factory to protest against its closure, police, operating with highly questionable legal authority, surrounded the offices and prevented supporters from joining the sit-in or food from being brought to the protestors. The recent occupation of Visteon also saw a heavy police presence both outside the plant and on the factory grounds. Both saw authorities mount very swift legal challenges to occupiers, with the threat of eviction and prosecution an important factor in the workers’ decision to leave. If the recent experience of the occupation of a Thomas Cook office in Dublin is anything to go by, where some 28 former employees were arrested in a dawn raid, these threats are to be treated seriously.

Brown has already made it clear in recent speeches that his government does not intend to bow to pressure from the trade union leadership to reintroduce secondary picketing rights or reform trade union law. With a wave of industrial action expected across the public sector, and workers increasingly turning towards wildcat activity, we can only speculate as to the tactics the state may be willing to employ to guarantee future labour discipline. Despite the assurances of leading economists that we are now entering a period of recovery, the challenges to the working class are far from over. Temporary stability has come at a high cost and many are facing unemployment, job insecurity and cuts in pay, alongside huge cuts in the “social wage” as the government is desperately attempting to claw back spending from public services. This is not even to mention the fact that many of the world’s leading financial industries are yet to dump their toxic assets. We can expect sustained and recurring crises as capital restructures itself, all of which is a recipe for social discontent. It was this, in fact, that was the true context for the original “summer of rage” comment: not the prospect of anti-capitalists swarming over the Square Mile for a couple of days, but analysts looking anxiously to the discontent in Greece, Italy and France in response to the recession. Whether we in fact got our promised “summer of rage” is open to debate. What is clear is that we can expect a long and protracted struggle over the future shape that capitalism will (or will not) take. The role that the police, and other aspects of the state’s legal apparatus, will play in this is all too clear.

G20 AND THE NEW CAPITALISM

The global economic crisis has been a moment of truth for everyone – politicians, capitalists and workers alike. For anarchist communists it’s a truth that’s been painfully obvious all along. Capitalism is not only unjust, it’s also wildly unstable, propelled by an inherent cycle of boom-and-bust in which periods of growth are inevitably followed by recession – and the bigger the boom, the more catastrophic the crash, as events of the last year have demonstrated.

Of course it’s always the working class who bear the brunt of the crash by losing our jobs, homes, benefits and pensions, just as it’s the working class whose labour fuels the bosses’ profits during the boom years. That’s why the ruling class during times of recession are usually content just to brazen it out: they may not be happy to see profits fall, but they’re prepared to wait until the next turn of the cycle when they can start making money again, and if they’re canny they can even use the opportunity to cut their costs and snap up a few cheap assets in the meantime. But this time the crash has been so catastrophic that even the capitalists have been forced to realise that some kind of fundamental change is required. The burning question for all of us is what that change will be, and whose interests it will serve. At a time when even the most un-politicised worker can plainly see that capitalism doesn’t work, the ruling class are desperately trying to convince us – and probably themselves – that capitalism will be able to adapt and survive. There will be change, they say, but it won’t be a revolutionary change to a new kind of society: it will be a change to New Capitalism.

“Values, development, regulation”

The phrase “New Capitalism” has been around for years, used by academics and commentators to refer to anything from consumerism to the rise of information technology, but it really came into its own in the wake of the 2008 crash, when panic-stricken journalists and politicians were rushing to make predictions or promises about what would happen next. One of the earliest and most enthusiastic adopters of this “New Capitalism” was Nicolas Sarkozy, who as early as October 2008 was touting the phrase around the EU. Sarkozy went on to co-organise (with Tony Blair) an international symposium titled “New World, New Capitalism” in Paris in January 2009 which brought together politicians, union leaders, international bureaucrats, financiers and academics. Then, on the opening day of the G20’s London Summit in April 2009, Sarkozy published a piece in the New York Times on “Forging the New Capitalism” in which he set out his vision for the future of the global economy.

So what is this New Capitalism, and how does it differ from the old capitalism? The subtitle of the Paris symposium sums it up in three words: “Values, Development, Regulation”. The values revolve around ethics and social justice. New Capitalism is going to have a moral basis. Rather than placing people’s happiness and wellbeing at the mercy of market forces, New Capitalism will be actively concerned with fairness and equality. In particular, it will focus on a fairer distribution of wealth and opportunities between rich and poor nations, which is why its second value is development. New Capitalism will reduce the gap between rich and poor, both within and between nations. In order to do this it will introduce a new framework of international regulation, rather than simply allowing globalisation to unfold as a process of unregulated free trade. Regulation will ensure global social justice, curb market excesses, prevent any repeat of the financial bubble which led to the current economic crisis, and ensure a return to “sustainable growth”. Regulation on this scale means not just a “return of the state” (as Sarkozy put it during the symposium) at the national level, but also the reinvigoration of international institutions.

“Recovery and reform”

New Capitalism was not simply on the agenda at the G20’s London Summit: it was the agenda. The “Global Plan for Recovery and Reform” set out in the Summit’s Final Communiqué is in perfect harmony with New Capitalism, even if it doesn’t explicitly use the phrase: every page of it has something to say about values, regulation and development. But the ways in which it does so are instructive, and tell us a lot about what New Capitalism really means.

The Communiqué sums up the G20’s plan in six commitments:

1. to “restore confidence, growth and jobs”;

2. to repair the financial system;

3. to strengthen financial regulation;

4. to reinvigorate international financial institutions, particularly the International Monetary Fund (IMF);

5. to promote global trade and reject protectionism;

6. to “build an inclusive, green, and sustainable recovery”.

As always, it’s the small print you have to watch, and an awful lot of the Communiqué’s small print turns out to be about the IMF. For decades the IMF has been notorious for its behaviour towards poor nations, on which it has imposed so-called Structural Adjustment Programmes which suit the demands of Wall Street but have disastrous consequences on poor nations’ economies. In 2008 the IMF looked like it was finally on the ropes, with its influence on the wane and its own internal finances in trouble. Now the G20 has restored the IMF to life, tripling its funding to $750bn and giving it a powerful central role in both stimulating and regulating global trade.

The Communiqué’s emphasis on support for developing nations through the IMF and other institutions re-affirms the centrality of development to New Capitalism, but in doing so it also reveals whose interests that development really serves. The Communiqué urges the IMF to continue its internal reforms, and singles out the new Flexible Credit Line (FCL) as particularly commendable. The FCL is effectively an overdraft facility for developing nations, designed to boost the economies of richer countries by getting poorer countries to import from them – in other words, to stimulate G20 states’ economies by putting developing nations in debt. This is certainly a change of sorts from the old days of the IMF, when Structural Adjustment Programmes made developing countries’ economies dependent on exports to the rich; now it’s trying to make their economies dependent on imports and consumption instead. So much for New Capitalism’s commitment to development.

The IMF also turns out to be key to New Capitalism’s ethical values – that “inclusive, green and sustainable recovery”. The “green” part of the recovery, as far as the Communiqué goes, was merely a bit of hand-wringing about rising oil prices and the need for “green business opportunities”; in contrast to its specific funding and policy agreements in relation to the IMF, the London Summit produced no environmental policies or commitments whatsoever, leaving it up to individual nation-states to take action. The “inclusive” bit was back to that key New Capitalist concern with development, with some more rhetoric, and some more money – for the IMF and World Bank.

So for the G20, New Capitalism’s commitment to development is about opening up new markets in developing countries; regulation is about the economic re-armament of massive international institutions to ensure that developing nations remain at the service of the rich; and values … well, values turns out to be not much more than a lot of window dressing and hot air.

New World?

New Capitalism, then, is an ideology: a set of ideas, in this case about sustainability and social justice, which distort or even hide the real power relations at work in the world. But New Capitalism is itself also a set of real power relations, involving states, institutions, markets and commodities which are all being dramatically reconfigured in the wake of the global financial collapse.

The triumph of New Capitalism is of course not guaranteed; Sarkozy and his allies have seized on it precisely because the economic crisis is threatening to hurl them out of their positions of global power – if not to destroy capitalism altogether, then at the very least to re-organise it drastically so that Europe and the US no longer call the shots. Having proposed a New Capitalist programme of reform, heads of state will now have to fight to make it stick, and to make it deliver the results they’re hoping for. Economic protectionism, the spectre of which is repeatedly invoked in the Final Communiqué and elsewhere, will be just one of the issues over which that fight will take place. International institutions like the IMF will be another.

Nation-states and international institutions are the means by which capitalists oppress the working class, but they are always also arenas where the ruling class plays out its own internal power struggles. This is certainly what is happening in the G20 at the moment, and it’s unlikely that all of the G20 leaders who endorsed the Final Communiqué did so out of a shared enthusiasm for Sarkozy’s New Capitalism. To put it bluntly, everyone’s playing an angle, and the return of the IMF is a case in point.

The Communiqué may praise plans for IMF reform, but it does not mention the wrangling that was already going on between the US and Europe over the form those reforms should take, nor the wrangling that leaders will now have to perform to raise the promised new IMF funds from their respective state treasuries. Even more significant, though, is the emergence of the so-called BRIC bloc of Brazil, Russia, India and China – the world’s most rapidly emerging economies – who want to use the IMF for purposes of their own. China has long wanted to displace the US dollar as the global currency and replace it with Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), the unit of account used by the IMF as a kind of internal “currency”. In June 2009 the BRIC countries held their first summit meeting and announced plans to switch some of their own foreign currency reserves (their national “savings accounts”) from US dollars to SDRs. So in increasing the power and wealth of the IMF, the G20 seems to have inflated a political football for an internal power struggle between the US and Europe on the one hand, and the BRIC countries on the other. If we are indeed destined for some form of New Capitalism, it won’t necessarily be on Sarkozy’s, or Obama’s, terms.

If the triumph of New Capitalism is not inevitable, what are the prospects for an end to capitalism altogether? At the Paris symposium in January 2009 it was no less a person than John Monks, General Secretary of the European TUC, who reminded participants of what had been happening on the streets of Athens just a few weeks before, and who warned of the danger of “social unrest” if economic recovery was not forthcoming. The fact that the ETUC was not just represented at the symposium, but was eagerly offering help and advice on how to avoid the overthrow of capitalism, tells us everything we need to know about the role of mainstream trade unions in working-class struggle. But the point is that working-class struggle is alive, and active, and angry. The current economic crisis, complex and contradictory as such historical moments always are, will continue to inflict hardship on working people, but it will also provide opportunities for solidarity, resistance and perhaps, ultimately, revolutionary action. Anarchist communists need to keep a weather eye on the manoeuvrings of New Capitalism, both to track its changing power relations, and to unmask and combat its ideology. But we all know perfectly well that no version of capitalism, New or otherwise, can ever form the basis of our New World.

THERE MUST BE SOME WAY OUT OF HERE

A Report from the Anarchist Movement Conference 2009

First off, a disclaimer: naturally, with any event, a report based on one person’s experience will be highly subjective and fail to adequately represent the whole thing, but this effect is sharply increased with an event like the Anarchist Movement Conference, where participants spent most of their time discussing in small groups, so people in different groups had vastly differing experiences. This report is not, and could not be, a definitive description of what the conference was like, or a statement of what the Anarchist Federation thought of it; it’s just an account by one participant.

First

of all, who was the conference for, and what did it hope to achieve?

The conference defined its target audience as “those opposed to

the state, all forms of nationalism, capitalism, sexual/race/gender

oppression and all forms of exploitation and domination”. In

practice, those who turned up were mainly class-struggle anarchists

of one form or another, with a healthy attitude to escaping the

anarchist ghetto and trying to build a genuinely effective movement

with some connection to the wider working class. Which isn’t to

say that it was entirely made up of class-struggle anarchists by any

means - there was a scattering of bizarre post-situationists who

declared that the working class was totally integrated into capital

and no longer revolutionary (they forgot to tell us who, if anyone,

was still revolutionary), as well as people newer to the movement,

who were just discovering concepts (like the centrality of class

struggle) that might seem totally obvious to the rest of us. The

latter, at least, were a welcome sign that the movement is still

attracting some new people to it.

The discussion over the course

of the weekend showed an encouraging commitment to examining our

practice with an eye to working out what works, not only examining

the glorious high points but also our (fairly frequent) failures,

such as the massive movement against the Iraq war, which was marked

by a double failure - both the failure of anarchists within the

movement to effectively challenge the authoritarian leftist

leadership of the movement and their passive liberal tactics, and,

partially as a result of that, the failure of the movement itself to

ever really pose a serious threat to the war drive. The topic of

sustainable activism and national vs. local campaigns was also

discussed, with a recognition that activity is most likely to be

effective and sustainable when it’s rooted in people’s

day-to-day lives, although it’s also certainly the case that we

can’t just fight capitalism on a localised basis. Within the

group I was in, the discussion went fairly smoothly and was run on a

fairly commonsense basis, although this was only possible due to the

vast majority of the group’s membership having a fairly similar

understanding of what anarchism means and a commitment to building it

in practice; from what I’ve heard, not every group was so lucky

(although several others were). Another key question was the

relationship of the movement to the working class as a whole - while

it’s true that the anarchist movement needs to be far larger

and stronger than it is, it’s also the case that the class

itself is coming out of a long period of defeat, so it’s

questionable whether the movement could be much better than it is

without a generalised increase in class consciousness taking place

first.

As with every other political discussion this year, the

utter mess that is our economy was also talked about quite a bit,

with a few practical initiatives being planned, such as the idea of

setting up support groups for workplace actions like the occupations

that have characterised so much of 2009; other concrete topics of

discussion included the lack of quality anarchist propaganda

representing the movement as a whole, instead of one particular

group, and the possibilities for improving Freedom

and Black

Flag

to be more representative of the entire movement. A proposal,

originating within the AF, for an anarchist directory of contacts,

was also circulated, and the Autonomous Students Network seems to

have become somewhat more lively since the conference took place.

It

would be utterly dishonest to write this report up without discussing

the No Pretence intervention, where the final session was disrupted

by anarcha-feminists seizing the stage to show a short film

highlighting the continued existence of male dominance and gendered

power structures within our supposedly anti-hierarchical movement;

this intervention inevitably generated fierce debate, and there

certainly isn’t an agreed AF position on the events, but as an

individual I thought it was brilliant, both in terms of the ideas

raised and the confrontational attitude taken. Without wanting to get

too complacent, I also think that the broadly supportive atmosphere

during the intervention, and the level of discussion afterwards, are

indicative of a movement that’s not cultishly afraid of

self-criticism, but can discuss its flaws and weaknesses

honestly.

So,

overall it went as well as could be expected. Several hundred

anarchists converged in London; we managed to find the venue and

spend a weekend talking to each other without anyone ripping anyone

else’s head off; and I think that pretty much everyone there

had their prejudices and expectations challenged at some point during

the conference. Still, Rome wasn’t built in a weekend, and

we’re not going to burn it down in one either, so the true test

of whether the conference actually meant anything, instead of just

being a fairly pleasant way to spend a few days, can only come as we

try out the ideas we discussed that weekend in ongoing struggles

around our day-to-day lives. See you on the streets!

CHINA: THE WORKING CLASS AGAINST ‘THE HARMONIOUS SOCIETY’

If we’re to believe the commentary to be found in the mainstream media, China is the economic powerhouse that will pull us through the global economic crisis. Though the economic slowdown which hit the country in late 2008 was widely reported, and led to claims that China’s meteoric rise was stalling, the country’s ‘recovery’ since has been the subject of many excited column inches. The growth of its economy in 2009 has been seen as part of Asia’s ‘astonishing rebound’ – or at least that of rising powers like China, India and Indonesia – by publications such as The Economist. The implications for world recovery and the balance of power are significant, it is argued.

Likewise you could be forgiven for thinking that the inhabitants of the world’s most populous country are increasingly enjoying the fruits of economic growth and the bright future that faces them. As has been well reported, automobile and electronic goods consumption in China is up, the Chinese are entering cyberspace in droves, and Western consumer outlets like Wal-Mart are springing up in Chinese cities. To the Chinese government, this is ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’, the ‘harmonious society’ of state propaganda marching along the path of success and development. The biggest threat to this picture of successful development seems to be ethnic tension and threats of regional secession: the rioting between Uyghur Muslims and Han Chinese earlier in the year received much more media coverage in the West than ‘mass incidents’ of a similar scale but which lack the racial element often do, and the same can be said of the unrest in Tibet last year.

However, what we want to argue here is that behind this picture of growth and success lies class conflict on a huge scale. The conflict between Chinese workers and their employers – along with their friends in the ruling Communist Party – has increased in intensity as the economic crisis has hit China, and has continued to deepen and continue as workers learn important lessons from struggles. This wave of struggle has continued well into 2009, and has yet to break.

China and the world economy

Though we may be familiar with the talk of China as a rising economic superpower, the tendency of the media to discuss the matter simply in terms of competing national blocs, with China playing the role of a growing threat to US hegemony, has meant that China’s overall role in the global economy is less well understood. While China certainly does engage in geopolitical rivalry with the US, and boasts rival financial, energy, and increasingly high-level manufacturing industries, the country also plays an important symbiotic role with the US and other western economies within the capitalist system. The relationship of mutual economic dependence between the West – the US in particular – and China has been important in recent years, as debt-fuelled consumption in the US served to stave off threatened crises at the turn of the century (most significantly following the collapse of the dot.com bubble). China’s export-driven manufacturing industries pumped out the commodities to meet this burgeoning demand, fuelling the growth of China as a centre for the accumulation of capital. Meanwhile Chinese capitalists increasingly became global players in the world of investment and credit.

It was not difficult to predict that the current financial crisis which began last year would have significant effects on China. The intricate practices of packaging, trading and reselling debt which laced the global financial industry led to the spread of risk throughout the system in a way which was nigh-on impossible to follow. As crisis quickly spread throughout the system, confidence fell away in the face of financial disaster. The subsequent collapse in growth and attempts to claw back wealth from workers through cuts and layoffs in the West led to a drop in consumption, and hence a drop in demand for China’s export-oriented manufacturing industries. China’s economy virtually stalled at the end of last year, leading to huge numbers of layoffs and a concurrent wave of struggles over sackings and unpaid wages. Through late 2008 China saw a fall in the rate of investment, a fall in economic growth, a fall in state income and a fall in output.

However, since then there has been much coverage of the upsurge in the fortunes of the Chinese economy in 2009. Between the first and second economic quarters GDP growth was up by 15%. Manufacturing output increased by 11% from July 2008 to July 2009. It has been argued by some that 2008’s downturn was only in part due to the export-oriented role of large sectors of its economy and the subsequent turbulence they experienced due to the global crisis. According to these commentators, it was also influenced by the explosion in the prices of oil and food pushing down levels of consumption, along with the Chinese government’s anti-inflationary money policies. As the scale of these problems declines, it is argued, China’s economy can pick up the pace once more.

On the other hand, other commentators argue that job creation and increases in purchasing power are largely non-existent, and that total spending is in fact being carried by a thin sector of the population – well paid urbanites – while the majority is frozen out of the economy. The Chinese government, less hobbled by debt than Western counterparts, has launched a huge fiscal stimulus package which has pushed up output artificially. The unused capacity in the Steel industry is equivalent to the steel output of Russia and the US combined, for example. Likewise the stimulus has functioned to create bubbles in real estate and the stock market. It is argued that all of this defers crisis for the sake of short-term recovery, or at least the appearance of it.

Either way, it is undeniable that the crisis had a severe impact on the living conditions of Chinese workers, with cities in export-oriented zones such as Dongguan being hit by huge waves of layoffs. The situation for Chinese workers has remained largely unchanged despite the changing fortunes of the economy. The question of the precise reasons for GDP growth becomes moot when one million workers out of Dongguan’s workforce of ten million have been sacked. Millions of migrant workers have returned to the countryside as job opportunities in the cities dry up, and the purchasing power of many working-class Chinese has been squeezed by wage cuts. What is vital, however, is that none of this has transpired without struggle from the working class in China.

A wave of struggle

According to the Chinese government, the first quarter of 2009 saw the highest number of “mass incidents” recorded to date. The euphemism refers to strikes, demonstrations, protests, roadblocks and the like which involve over 25 people. The state claims there were 58,000 such incidents in the quarter, and should the trend prove to be consistent throughout the year, 2009 will have been the most volatile since records began, with nearly twice as many incidents as the year before. While information can rarely be taken from the Chinese government on trust, the fact that unrest is building in China is undeniable, with large struggles over layoffs, withheld pay, land seizures, corruption, pollution and so on occurring on a daily basis, alongside strikes, occupations and protests over a range of workplace grievances.

News of much of the unrest has barely filtered through to the West, with the exception of certain high-profile incidents. The killing of a boss by an angry mob in Tonghua in the north-east of the country during the rioting which accompanied a takeover of a steelworks was one such incident, an incident which also saw 30,000 steelworkers battle riot police.

Nonetheless, the broader trends are observable to those able to carry out the research. In recent months China Labour Bulletin has published a report which examined 100 struggles, and found that workers are increasingly acting autonomously, and becoming powerful enough to force the government to intervene and end the dispute. Moreover, struggles are consciously being spread and replicated, with protests moving throughout regions like wildfire. On top of all this, workers are frequently going on the offensive, making demands in their own interests rather than just carrying out defensive struggles as confidence increases.

One important aspect of developments covered by the report has been the fact that workers are often bypassing the official trade union bodies altogether. Trade unions in China form little more than another layer of the state apparatus, locking workers into government and party manoeuvrings. The sole trade union organisation in China is the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). With 174m members, it is the world’s largest trade union organisation. The ACFTU unions frequently run closed-shop arrangements, and the organisation of independent, competing unions is illegal. The ACFTU has deep ties to the ruling Communist Party, and participates in the implementation of government strategies and policy goals in industry. Moreover, it makes no secret of this, recently making public its “five-faceted and unified” plan for the protection of workers’ rights: “1.leadership of the party, 2. support of the government, 3. cooperation of society, 4. operation by the unions and 5. participation by the workers”. These points were ranked in order of importance.

What this means in practice can be seen in a recent case. When workers in Shaanxi attempted to set up a congress which would seek to put workers in control of unions and shopfloor organisation, the ACFTU swung into action, threatening the workers involved and claiming that the congress was a “reactionary organisation.” According to ACFTU officials, the congress was an attempt to destroy China’s “harmonious society”, and was being controlled by foreign interests.

Unsurprisingly, workers are increasingly seeing the ACFTU as part of the problem, not the solution, and have been attempting to bypass it altogether. They have sought to spread their struggles, causing enough trouble to disrupt the normal functioning of society and force the government to intervene, leaving the official unions and their petitioning tactics far behind.

A recent example of such developments is that of the taxi drivers’ struggles which have swept the country since 2008. Taxi drivers in Chongqing - who had previously been subject to repression when organising autonomously - went on strike en masse in November 2008. Faced with 10,000 workers undertaking determined action, the government changed its approach and sought to placate the strikers. After initial threats of repression, it ruled that their treatment was illegal and enforced their demands on employers. Following this victory, copycat strikes spread throughout the country, with drivers in Hainan and Gansu provinces beginning stoppages over similar grievances. In Yongdeng, a county in Gansu, the drivers blockaded the offices of the traffic bureau. Again, the government acceded to their demands. Fujian and Guangdong provinces were hit next, once again forcing the government to impose the demands on employers in order to stave off further unrest and to stop the struggle spreading further. The wave of strikes spilled over into December, with drivers in Guangzhou stopping work en masse. More mass taxi driver strikes have occurred this year, with 5,000 out in Qinghai province in June. Chinese taxi drivers have discovered that they didn’t get their demands met by petitioning officials, but by terrifying them.

Other workers have made use of similar tactics. In November last year 7,000 factory workers in Dongguan - a major manufacturing centre - went on strike, occupied their workplace and blockaded roads after three months’ pay was withheld. The government was faced with paying the wages or the risk of unrest spreading through the city, and coughed up the money.

This wave of struggles has continued into 2009, and such incidents are happening at a higher rate than ever before. It is clear that workers are learning from their experiences, and their tactics are developing accordingly. They are taking control of their own struggles, and leaving behind the official unions as the dead weights they are.

Where next?

Though these are important developments, and show the potential for a movement of the working class acting in its own interests, they have not yet come near to challenging the ongoing rule of the party or threatening capital in a significant sense. The state is still capable of cracking down on organisers and militants, and has handed down lengthy jail sentences to those involved in strikes and protests in recent years. Even if it is currently finding that backing down may be safer than attempting to crush struggles in many cases, it would certainly swing into action in the most brutal way if it felt seriously threatened.

On top of this, it is unclear whether the image of the Communist Party as a party of paternalistic ‘socialists’ trying their best to look out for the interest of workers and peasants has been significantly dented. The belief that the Communist Party is doing its best for the ‘Chinese people’- despite events and developments - is common. Workers still articulate struggles of the most confrontational type with reference to the revolutionary heritage of the Communist Party. For example, during a demonstration by factory workers in Liaoyang in 2002 which demanded the release of imprisoned workers’ representatives and the sacking of the Liaoyang Party Secretary, and which saw the attendance of between 30,000 and 80,000 people, workers lined up behind a huge portrait of Chairman Mao as they marched through the city. More recently, authorities have attempted to contain protests and struggles by focussing attention on inept local officials and party representatives, so as to draw attention away from more systemic problems.

Just as it is important that workers break with any illusions in the Communist Party, it is also important that any alternative political perspectives that arise do not gain new illusions in Western-style democracy. While rights snatched from the state in the course of struggle are important, they are meaningless without the collective clout to enforce them on employers and the state. It would be a disaster if Chinese workers were to discover their power only to invest it in the cause of re-organising state capitalism in favour of a less severe-looking set of ‘democratic’ rulers. Russians have had to learn this lesson the hard way, as the fall of the Communist Party in that country has led to a collapse in living standards, incomes and employment for the majority of the population and the rise to power of a new ruling class of billionaire oligarchs as transparent in their self-interest as their ‘red’ predecessors.

An alternative political perspective is vital. This perspective must reflect the developing grassroots power of the working class in China, and maintain a perspective focussed on imposing change on employers and the state through direct action and solidarity. Consciousness develops alongside struggle, and we are seeing increasing confidence accompanying snowballing unrest. Radical new perspectives are not impossible, and are not without precedent in China. Any major unrest which threatens the rotten state-capitalist system must be accompanied by an outlook which maintains a healthy distrust of employers, the unions and officialdom alike. Only with such an understanding does the working class in China and around the world stand a chance of escaping the ongoing disaster that is capitalism.

OCCUPATIONS OF THE LAND, OCCUPATIONS OF THE WORKPLACE: a brief history

“We must bear in mind that no government, however honourable, can decree the abolition of misery. The people themselves – the hungry and disinherited – are they who must abolish misery, by taking into their possession, as the very first step, the land which by natural right, should not be monopolised by a few but must be the property of every human being... What you need is to secure the well-being of your families – their daily bread – and this no government can give you. You yourselves must conquer these good things, and you must do it by taking immediate possession of the land, which is the original source of all wealth. Understand this well; no government will be able to give you that, for the law defends the “right” of those who are withholding wealth. You yourselves must take it, despite the law, despite the government, despite the pretended right of property.” – Ricardo Flores Magon, Mexican anarchist

This article will look at the history of occupations, both of the land by peasants and rural workers and of workplaces by those who work in them. It will show that there is a long tradition of such occupations, and that far from being dead, wherever workers and peasants need to reply in a strong way to the greed and callousness of the boss class of land and city, occupations are still an effective means of struggle.

The Land

It was in April 1649 that the Diggers, inspired by the teachings and writings of Gerrard Winstanley, began their occupation of wasteland at St George’s Hill near Weybridge in Surrey and called on all poor people to join them or follow their example. This was one of the first recorded examples of seizure of the land so that it could be worked in common. Following physical attacks by gangs organised by the local landowners, the Diggers were forced to move to nearby Little Heath. They were driven from there too by similar means. Another Digger community which occupied common land at Wellingborough in Northamptonshire was harassed by the authorities and several of its members arrested. Other Digger occupations of the land took place in Iver in Buckinghamshire, Barnet in Hertfordshire, Enfield in Middlesex, Dunstable in Bedfordshire, Bosworth in Gloucestershire, and in Nottinghamshire. By the end of 1650 all the land occupations appear to have been broken up by local landowners or by the actions of the Cromwell government and its armed forces.

In the lead-up to the French Revolution there was increasing encroachment on common land by the lords, with laws being passed to grant them a third of such land. With the Revolution of 1789 the tide turned, and new laws were passed to attack the rural seigneurs. However this went against the ideas of the bourgeois revolutionaries leading the French Revolution, who strongly believed in individual property whilst being opposed to the monarchy and aristocracy. As a result any recovery of common land seized by the aristocrats was suspended in 1796. However no active occupation of the land seems to have occurred during the Revolution.

During the Mexican Revolution which began in 1910, the subject of land occupation came firmly onto the agenda. Under the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz a great amount of land had been seized from the peasants for the big landowners. In the south, Emiliano Zapata and the Liberation Army of the South called for radical redistribution of the land under the slogan “Tierra y Libertad” (“Land and Liberty”), and began to carry this out. The call was taken up by Zapata’s allies throughout Mexico, including the forces of Pancho Villa in the north. The Zapatistas destroyed all land records in the villages they occupied, and the haciendas (big estates) were handed over to the peasants. In Morelos State, 53 such haciendas were given back to the workers of the land. The defeat and institutionalisation of the Revolution and the murder of Zapata in 1919 ended the radical redistribution of land. However in areas where peasant organisation remained strong and where they defended land with arms, the governments of the 1920s and 1930s entered into alliance with them against the landed gentry and to further their own aims of nationalisation of resources. In this process the government increasingly sabotaged independent peasant organisation by their strenuous efforts to integrate them into a movement of support for the government.

During both the 1905 and 1917 Revolutions in Russia, peasants took a major role in seizing land. In 1905 the condition of the Russian peasants was dire. Land seizures took place, sometimes followed by looting and burning of the houses of the big landowners. Illegal logging and hunting on land owned by the aristocracy also took place. Three hundred districts of 47 provinces were affected and 1,000 manor houses were burned down during the three months from October to December 1905. The unrest did not end with the events of 1905 but continued into 1906 and right up until 1908. Government concessions given in 1905 were seen as a green light for the redistribution of the land, so attacks took place with the aim of forcing landlords to flee. These actions were answered with massive repression from the authorities.

Similarly in 1917 peasants began mass land seizures, most significantly in areas like the province of Tambov in the east. In some areas communal working of the land was inaugurated. However, the hostility towards the peasantry of the Bolsheviks – who at first exploited the slogan “The Land to Those Who Work It!” – resulted in grain seizures, mass terror, and finally to forced collectivisation rather than the free collectivisation of the land that could have been achieved by the peasants themselves. As the anarchist Peter Arshinov noted in his History of the Makhnovist Movement:

The peasants made good use of the land of former pomeshchiks (land-owning gentry), princes and other landlords. However, this well-being was not given to them by the Communist power, but by the revolution. For dozens of years they had desired the land and in 1917 they took it, long before the Soviet power was established. If Bolshevism marched with the peasants in their seizure of the pomeshchiks’ lands, it was only in order to defeat the agrarian bourgeoisie. But this in no way indicated that the future Communist power had the intention of furnishing the peasants land. On the contrary. The ideal of this power is the organisation of a single agricultural economy belonging altogether to the same lord, the State. Soviet agricultural estates cultivated by wage workers and peasants – this is the model for the State agriculture which the Communist power strives to extend to the entire country.

In Italy, whilst factory occupations are more remembered from the Red Years of 1919-21, parallel occupations of the land were happening in the south. Anarchists like Camillo Berneri have argued that these land occupations were more radical than those in the factories in the north. The Fascist squads were used against the land occupations just as much as they were against those in the workplaces in the period of reaction that ended the revolutionary wave in Italy.

From March 1936 onwards, during the Spanish Revolution, 60% of land in the area outside of Francoist control was rapidly brought under collective working, with 2,000 anarchist agricultural collectives totalling 800,000 people. The Revolution on the land was more sweeping than in the towns.

Throughout the rest of the world land occupations have been no less important, particularly in the years after the Second World War. For example, in the Telangana region of Andhra Pradesh in India, massive land occupation against the local landed elite took place which was only crushed with the intervention of the Indian Army in 1948. In South Africa in the 1980s one of the forms of struggle against the apartheid regime was occupation of the land, a necessity for many landless agrarian workers who were being robbed of livelihood and sustenance. Under the new regime the land struggle continues – as it does in neighbouring Zimbabwe, where the occupation of the white farmers’ land has been institutionalised by the Mugabe regime. ZANU-PF and the state have made strong efforts to co-opt, contain and control the land occupation movement, using it as a weapon in their own war against their political enemies. Former guerrillas have been integrated into the regime and play a leading role in this movement. Criminal elements and those intent on opportunistically grabbing land for themselves are also present. There remains the possibility of independent peasant organisation breaking with this state- and ZANU-PF-controlled movement, which itself has been responsible for the death of many black agricultural labourers

Land occupations are spreading throughout Latin America from Paraguay to Mexico. A movement of land occupations began in Brazil as a result of intense pressure on agrarian labourers and peasants. Entwined with this was the development of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST) – the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement – which had its roots in the 1970s, and which emerged in the 1980s and orientated itself to the land occupations. At first the MST was controlled by liberation theologists of the Catholic Church. It then came under the control of Maoists and social democrats from the old left parties. It is a bureaucratic and highly centralised organisation, seeking to demobilise genuine land occupations and sidetrack them into rural shanty towns. It is allied with the Brazilian state and offers an internal market solution, laced with strong doses of economic patriotism. The rural uprising in Brazil will have to break with the politics of the MST.

As we have seen, the movements for land occupation have to develop an independent and autonomous politics and free themselves from the machinations of state manipulation and the rackets of political “vanguards”.

The Workplace

The occupation of factories was launched in Italy in the years just after the First World War. A massive movement to occupy and run the factories started to get underway in the big industrial centres of the north like Milan and Turin. Internal commissions sprang up, each based on a group of people in a workshop with one mandated and recallable delegate for every 15-20 workers. These in turn set up their own internal commisions which became known as factory councils. In 1920 this became a mass movement, and occupations began after the bosses attempted to oppose changes in conditions and pay. Metal and shipbuilding workers in Liguria occupied and ran their workplaces for four days. Anarchists were among the first to suggest occupying the workplaces. This was taken up on a wide scale in the anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist movements, both of which had seen a massive increase in size in the immediate period after the First World War.

This brought a counter-attack from the bosses, who sought to ban the factory councils from the shop floor and limit their meeting outside of work hours. This move was defied by workers. When several council delegates were sacked, a new wave of occupations began. Bosses responded with a lockout and the appearance of armed troops outside the workplaces. A general strike, solid in Turin, broke out in response to the repression. At its climax the strike involved 500,000 workers. Railway workers in Pisa and Florence refused to transport troops to Turin. In September there were more massive occupations. Strikes spread to engineering factories, railways and road transport, with peasants also seizing land. The occupying workers began production for themselves under their own control. Italy was paralysed, with half a million workers occupying their factories and raising red and black flags over them. The movement spread. But after a month the movement was sold out by the Socialist Party and the unions it controlled. This major defeat resulted in the rise to power of Mussolini’s Fascist movement as big employers poured large sums of cash into its coffers in an effort to deal a mortal blow to the workers’ movement.

In France, the threat to the French Republic from the far right paramilitary ligues, and their attempted overthrow of the government in February 1934, combined with a deep economic depression, resulted in a wave of protest from the workers’ movement which drew in both the Communist Party and the Socialist Party. A Popular Front government under the leadership of the Socialist Léon Blum was set up after the electoral victory of April 1936. This sparked off an unprecedented strike wave in May and June, which included occupations of the factories. In the countryside, land occupations also began. The government conceded something that had not happened before – paid holidays, a 40-hour week and other reforms (necessary for the modernisation of capitalism). But at the same time collective bargaining was agreed upon by the main unions and the Communists – a sell-out of the strikes and occupations movement, and a diversion from far more radical possibilities. This was harshly criticized by anarchists and other revolutionaries. The flight of capital and other economic problems led to the resignation of Blum and the collapse of the Popular Front in 1937. Once again the Socialist and Communist Parties had sabotaged a movement.

Thirty years later in May 1968, a massive uprising began with barricades being built in the Latin Quarter of Paris. Initially the movement only involved students, but it quickly drew in many other people. The largest general strike in an advanced western economy, one that was not called by the union centrals, broke out. The events highlighted the malaise within France, which had been ruled by a Gaullist administration for many years. Eleven million workers, about two thirds of the overall workforce, were involved in this movement at one time or another.

Following large demonstrations and street fighting, the Sorbonne college was occupied in mid-May. This was followed by the setting up of hundreds of occupation committees throughout France. It was echoed in the action of workers, who began occupying factories, starting with a sit-down strike at the Sud Aviation plant near Nantes, followed by another strike at a Renault factory near Rouen which spread to the Renault manufacturing complexes at Flins in the Seine valley and the Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. By 16th May workers had occupied around 50 factories, and by 17th May 200,000 were on strike. That figure snowballed to 2m workers on strike the following day, and then 10m, or around two thirds of the French workforce, the following week. However once again the movement was sabotaged by the Communist Party and the unions it controlled. This, coupled with the brutal attacks launched by the French state, brought the movement to an end.

The movement and previous examples of occupations had not completely disappeared from French workers’ consciousnesses, however. As a result of their discovery of plans for huge restructuring and mass sackings at the Lip watch factory near Besançon, workers once more went into occupation with a work-in in 1973. One hundred thousand people demonstrated in support at Besançon. Eventually, in what was seen as a victory, the factory was taken over by a finance capitalist, and the entire workforce was re-employed, ending the occupation. Things did not end there though. The incoming right-wing government led by Chirac was determined to punish the Lip workers. The new owner was forced out, and the attacks on workers began again in 1976. Another occupation began, ending with the workers setting up a co-operative involving 250 of the original 800 workers. This collapsed in the 1980s.

The tactic of factory occupation spread throughout Europe in this period to Belgium, Holland and Switzerland. It was often employed by Italian workers during the years of unrest in the 1970s. It was widely used during the Portuguese Revolution of 1974 and the overthrow of the Fascist regime there. It even spread to Britain: Briants (April 1971), UCS in Glasgow (July 1971), River Don Works (October 1971), Fisher-Bendix (January 1972), Linpac in Liverpool (March 1972), BLMC in Cowley (April 1972), Lovell’s in London (May 1972), and Westinghouse Brake and Signal Co. in Wiltshire (May 1972) – more than 200 factory occupations occurred up to 1976. Most of these were around five major industrial cities – Glasgow, Liverpool, Sheffield, Manchester and London – although occupations also occurred in rural areas like Fakenham and Great Yarmouth in Norfolk. This was in a period of major factory closures and sackings. Over 150,000 workers took part in these actions over that period. However the occupations remained under the control of the unions, and their Labour and Communist Party officials failed to take the offensive and generalise the struggle, ending in various deals where some jobs were saved.

The Present

It might have seemed that workers’ militancy had passed – if you were mug enough to believe the propaganda onslaught in the ruling-class media of the last decade or so. Now workplace occupations have started rearing their little heads, snowdrops pushing through the soil. The Obama administration received a welcome with the occupation of the Republic Window and Door factory in Chicago, the first sit-in strike the USA has seen for decades. In Ukraine, workers occupied a harvesting machine factory in Kherson. In Poland a Thomson factory was occupied, in Ireland it was the turn of the crystal factory at Waterford, in Scotland it was the Prisme factory in Dundee, in London it was the Visteon factory, and more recently it was the Vestas factory on the Isle of Wight. Alongside this were the occupations of threatened schools in London and Scotland.

It looks like workplace occupations are returning with a vengeance. When bosses get into difficulties, particularly in times of economic crisis, they attempt to cut and run at the expense of workers. But workers are resisting with tactics of direct action. However, workers cannot let themselves be trapped inside the factory. They need to spread the struggle and gather support from other workplaces and from their neighbourhoods. As we said in a recent London AF pamphlet on the Italian factory councils:

The struggle was too confined to the factories and workshops themselves, and not enough was done to move mass action to the streets… The factory councils were an expression of the skilled and semi-skilled industrial working class, they did not represent and vocalise the interests of other sections of the working class, and were therefore an expression of a minority of the class.

We are far from the revolutionary situation that existed in Italy in the early 1920s, but we should still try to widen the struggle and develop a strong support movement for the occupations that can move outside the stranglehold of the unions and the so-called labour movement.

SURREALISM: A GOLDEN BOMB

“The mere word ‘freedom’ is the only one that still excites me … Imagination alone offers me some intimation of what can be.”

—First Surrealist Manifesto

“All power to the imagination!”

—Surrealist and Situationist slogan

It’s commonplace nowadays for anarchists to cite the Situationist International as important political forebears, and to use Situationist ideas in their political analyses. But there is far less understanding or appreciation of the movement that arguably gave birth to it: Surrealism, a genuinely international revolutionary movement which predated the Situationist International by several decades, has outlasted it by even longer, and continues with unabated fury today.

The claim that anarchists are ignorant of the Surrealist movement might seem at first glance to be an odd one, given the enormous volume of books, exhibitions and TV documentaries on the history of Surrealism which cultural pundits continue to churn out – not to mention the extent to which the word “surreal” has entered everyday language as a synonym for “bizarre” or “zany”. The problem is that almost all of these representations of Surrealism, academic and popular alike, are gross misrepresentations of the movement’s principles and trajectory. So let’s start by listing a few of the things that Surrealism is not. It’s not a 20th-century art movement. It’s not an artistic or literary style. It is not a precursor of, or identical with, postmodernism. Salvador Dalí was not its greatest exponent (he was expelled from the movement in 1939 for his betrayal of its basic values), and André Breton was not acclaimed as its “Pope” (the epithet was coined as a vile insult by Breton’s enemies). It was and is not restricted to Paris, or to Europe, and it did not end in 1945, 1966, 1969, or any other date you may have read. In fact today there are active Surrealist groups in cities all over the world, including Athens, Buenos Aires, Chicago, Istanbul, Izmir, Leeds, London, Madrid, Montevideo, Paris, Prague, São Paolo, St Louis and Stockholm, as well as scores of individual Surrealists working alone or in collaboration with others.

Surrealism’s participants are passionate in their devotion to their cause, which aims to re-enchant and revolutionise everyday life. It’s a revolutionary movement not just in the sense of social revolution – much less artistic revolution – but total revolution, a transformation of reality at every level. For this reason it can perhaps best be characterised not as a cultural movement, or even as a philosophy, but as a quest for truth.

The poetic storm

The truth Surrealism is seeking is not the factual truth of “reality” as defined by the social or natural sciences, or indeed by most revolutionary political analysis. The utopian philosopher Ernst Bloch, a major influence on recent Surrealist thought, sums it up:

Is truth a justification of the world or is it hostile to the world? Isn’t the whole existing world devoid of truth? The world as it exists is not true. There exists a second concept of truth which is not positivistic, which is not founded on a declaration of facticity, on “verification through the facts,” but which is instead loaded with value – as, for example, in the concept “a true friend,” or in Juvenal’s expression Tempestas poetica – that is, the kind of storm one finds in a book, a poetic storm, the kind that reality has never witnessed, a storm carried to the extreme, a radical storm and therefore a true storm. And if that doesn’t correspond to the facts … in that case, too bad for the facts.

Surrealism is a quest for the true storm: the value-laden kind of truth which is truer than facts, logic or rationality because it tells us not merely what is, but what can be – the truth, in other words, of the imagination. The imagination is therefore both Surrealism’s research instrument and its field of investigation; and because it reveals to us what can be, the imagination is also the truest realm of freedom. Thus truth, freedom and imagination are indivisible, and their indivisibility is manifested in poetry – not poetry in the mundane sense of lines on a page, but in the deeper Surrealist sense of poetic truth, a kind of illumination which Surrealists also refer to as convulsive beauty, surreality or, more often, the Marvellous.

The annihilation of the distinction between apparently contradictory states, such as that between truth and poetry, has been the central principle of the Surrealist movement ever since the First Manifesto of 1924: in all the decades of activity since then, in all the different locations and historical, social and political contexts in which it has been conducted, this ongoing quest for the Marvellous has been what gives the movement its unity and purpose. As the Second Surrealist Manifesto (1930) famously puts it:

Everything tends to make us believe that there exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions. Now, search as one may one will never find any other motivating force in the activities of the Surrealists than the hope of finding and fixing this point.

Dreams and play

The Marvellous, then, is the point where contradictions are transmuted, the rules of logic implode, and the unity of truth, imagination and freedom is manifested. The most important fault lines upon which Surrealism operates are therefore the contradictions not just between real and imagined, but also between conscious and unconscious, sleeping and waking, and subjective and objective. This is why Surrealists have always been preoccupied with dreams – not because they simply love “bizarre” images for their own sake, but because dreams occur, precisely, at the vanishing point between all those contradictions. Dreams therefore offer a privileged point of access to the Marvellous, and are both cherished (most Surrealists keep a dream diary as a matter of course) and interrogated (Surrealists often experiment with different forms of dreaming, including collective dreaming and lucid dreaming). Other such privileged points of access include practices of automatism, ranging from automatic drawing and writing to musical improvisation and even dance; encounters with “found objects”; and experiences of “objective chance”, where extraordinary and sometimes prophetic coincidences obliterate the dichotomy between objective, “external” events and subjective, “internal” significance and meaning.

Surrealist investigations into these phenomena are rigorous and experimental, and usually take the form of play – sometimes in organised games, which can be more or less elaborately planned in advance, and sometimes in more spontaneous outbreaks of sheer playfulness. (Such playfulness is evident, for example, in the practices of détournement and the dérive, both of which were being explored by Surrealists before their adoption by the Situationists and continue to be developed and refined by Surrealists today.) Play is Surrealists’ favourite mode of research at least partly because serious play as such operates at that vanishing point between real and imaginary, conscious and unconscious. It also expresses Surrealists’ furious rejection of work, duty, usefulness and all those other “adult” values which represent compromise and defeat at the hands of a disenchanted and immiserated world. Play with others also revolves around the core Surrealist value of collectivity: Surrealism is often described as a “collective adventure”, and the practices of joint enquiry and shared experience have been essential throughout the movement’s history. Working collectively is not just a way of expressing solidarity and sparking ideas; opening up one’s own unconscious and putting it into direct communication with those of one’s comrades constitutes a radical experiment in breaking down the barriers between subjective and objective, and can be a transforming (and sometimes terrifying) adventure in its own right.

Surrealism and revolution

Facts are hostile to truth, and surreality is more real than reality; truth, imagination and freedom are indivisible, and the Marvellous is their manifestation. Clearly, Surrealism is a revolutionary movement in more than the usual sense of the word. But contrary to the widespread accusation that they are apolitical dreamers or, even worse, well-meaning political idealists, most Surrealists are acutely aware of the burning need for revolutionary action in the factual world here and now. Imagination may give us glimpses of what can be, but real-life revolutionary activity is required to get us there. In the words of Benjamin Péret: “This urgently-required, indispensable revolution is the key to the future … A poet these days must be either a revolutionary or not a poet.”

The Surrealist movement today is justly proud of its heritage of revolutionary consciousness and action. From Péret fighting with Durruti in Spain, to Claude Cahun’s Resistance activities on Occupied Jersey; from the courage and persistence of the Prague Surrealist Group under Stalinism, to that of Surrealists living under vicious dictatorships in southern Europe and Latin America; across a whole range of revolutionary commitment as anarchists, Marxists, Trotskyists, street-fighters and insurrectionists of every kind, Surrealists have played passionate roles in resistance and social action, and continue to do so today.

The current political composition of the international Surrealist movement is a mixture, broadly speaking, of Marxists (often, though not exclusively, Trotskyists) and anarchists (including communists, syndicalists, Wobblies, primitivists and anarcha-feminists). With such a mixture of revolutionary perspectives, it’s no surprise that internal political debates within the movement are frequent and often heated. Nonetheless it remains a matter of principle that the movement as a whole does not toe any party line or subordinate itself to any one political viewpoint or programme. This Surrealist rejection of dogma even extends to Surrealism itself. The commitment to poetic truth is an unshakeable fundamental principle, but all other practices and ideas, including those of Breton, are constantly tested and questioned. There is no such thing as orthodox Surrealism.

Surrealists recognise the urgent necessity of social revolution and the overthrow of capitalism, and many of them are active participants in revolutionary struggle. But they insist no less furiously on the urgent necessity of poetic truth, imagination, freedom, and the total transformation of reality. Indeed, for Surrealists the seeming dichotomy between poetry and political action is just as false as all the others: poetry is the practice of freedom, and vice versa. On the table in my parents’ house lies a golden bomb, with a live caterpillar for its detonator. Social revolution alone just isn’t going to be enough.

Suggested further reading:

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, Ann Arbor Paperbacks, 1972.

Michael Löwy, Morning Star: Surrealism, Marxism, Anarchism, Situationism, Utopia, University of Texas Press, 2009.

Michael Richardson & Krzysztof Fijalkowski (eds), Surrealism Against the Current: Tracts and Declarations, Pluto Press, 2001.

Penelope Rosemont (ed.), Surrealist Women: an International Anthology, Athlone Press, 1998.

Ron Sakolsky (ed.), Surrealist Subversions: Rants, Writings & Images by the Surrealist Movement in the United States, Autonomedia, 2002.

Some Surrealist groups’ websites in English:

Chicago Surrealist Group –

www.surrealistmovement-usa.org

Leeds Surrealist Group –

leedssurrealistgroup.wordpress.com

London Surrealist Group –