Confessions of a Peace

Thug:

Shannon and Direct Action

One year in the campaign to demilitarise Shannon, a

civilian airport, now used by the USAF.

This is a personal report of my own participation and

observations, so of necessity it is strong in some areas – the various

demonstrations at Shannon, and weak in others – the peace camp, the

surveillance. Of course most of what I have been doing in the campaign to

demilitarise Shannon has been helping to organise meetings, and leafleting,

organising helping to organise buses, and sticking up posters, and running

another bus, and sticking up posters, and sticking up posters, and sticking up

posters and oh yeah did I mention sticking up posters?.

So needless to say this report has been a bit "sexed

up", with little emphasis on the humdrum grunt work and more on the those

rare moments of adrenalin rush, with special reference to that one glorious

piece of mass destruction on October 12th.

I was first down in Shannon in mid August last year. We were

only about 70 strong, yet we defied police orders to stay outside the airport,

and by entering caused a warplane to leave without refueling. On August 31st

there was a 24 hour women’s peace camp outside the airport, with an

information stall in Shannon town itself which got a good reception. On

September 1st there was a small picket outside the main terminal

building. Also at this time two American warships carrying ammunition to the

Middle East were due to stop over in Cork Harbour, but this visit was cancelled

because of planned protests. On the night of September 3rd Eoin

Dubsky went into the airport grounds and re-decorated a warplane. I am normally

critical of this sort of "ploughshares" type action but it led to the

undeniable truth is that this was a massive advance in building a serious

anti-war mobilisation - . That is to say a movement which aimed to, at least to

some degree, grasp the problem with both hands and sort it out.

| Empirical evidence bears this

out – within one month the numbers protesting at the airport increased

tenfold. Shannon became a public issue. On October 12th

hundreds of people turned up to demonstrate at the airfield, and after a

fence was surgically struck and decommissioned by a small mob, one woman

darted across the runway grounds pursued by Keystone Cops. After a

pregnant pause she was followed by well over a hundred, who soon faced

threatened use of water cannon and police dogs, dogs and arrest. Ten

people were arrested, but released after the people occupying the runway

grounds refused to move until they ere released arrestees went free. After

, after the airport road was briefly blocked, and after we all went down

to the cop shop to make sure they would get out. |

|

Shortly after this the Third Grassroots Gathering took place

in Belfast. This brought together over one hundred environmentalists,

anarchists, and other assorted troublemakers from across the island and beyond.

There were almost 20 different workshops on a wide variety of topics including

Gender, Direct Action, Social Centres, Reclaim the Streets, Sectarianism, and

Forest Gardens. Long and laborious meetings at this event sought to co-ordinate

an autonomous strand within the peace movement with an orientation towards

direct democracy and action. We announced a ‘day of action’ on December 8th.

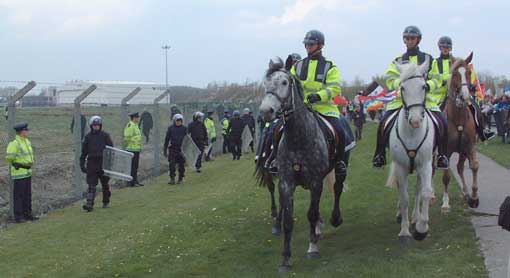

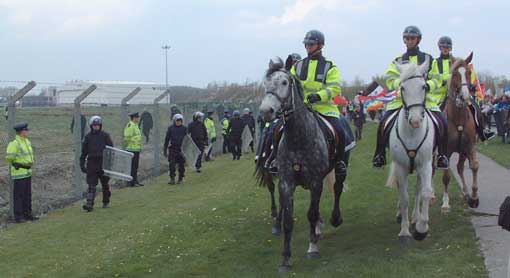

That day a diverse throng of around 400 demonstrators gathered in Shannon,

accompanied by 200 Garda (on two shifts), the Garda canine unit, undercover

police, Special Branch, a police helicopter and Aer Rianta’s own security.

Well we must be doing something right. We set off on a long trek to the airport,

complete with music from a shopping trolley sound system and fiddle player.

Strangely absent were mass produced placards bearing the same slogan, so people

had to make do with D-I-Y banners, homemade T-Shirts, one coffin with ‘Irish

Neutrality’ written on it, various Uncle Sam/Dubya impersonators, and a bunch

of kids chucking flour about the place. A team of graphic design artists went to

work on the truly crass 1970s tail fin monument near the terminal building -a

piece of public "art" that seems to plead ‘paint me!’, ‘paint

me!’, in a whimpering despair filled voice every time you pass it. It was

briefly transformed into a memorial to the recently deceased anti-war activist

Philip Berrigan and to the Iraqi children slain by UN sanctions and the US war

machine. Despite names being taken there were no arrests.

After a wee bit of a hibernation over the hols the new year

saw an avalanche of escalation. A permanent peace camp was set up. On January 18th

thousands traveled to the airport.

The best thing about that day was the spontaneity, which was

also perhaps the worst thing! I’m a great believer in the power of chaos but

after you occupy the rooftop of a derelict building before breaking into ….a

hanger? No a cafeteria stockroom! Yes that’s the day you know throwing a dash

of organisation into the pot just might improve the taste. Just a dash mind.

But it was all great craic. Although people have dissed the

rooftop occupation as a bit pointless, we had dodged police dogs to get on to

the roof so the disgruntled look of disgust as we gazed down upon the bacon, was

a pleasure to behold. No one was nicked on this occasion. The demonstration and

peace camp had a sizable impact. World Airways – one of the charter companies

ferrying U.S. troops through Shannon – took the decision to re-route 17 of

their flights to Frankfurt in Germany. A posse of peaceniks permanently camped

on the doorstep were not a reassuring sight to the suits in the corporate

boardrooms. And as a result, the government had to make Shannon safe for

Washington. Injunctions were brought against peace campers. One answer came when

Mary Kelly did a bit of D-I-Y on a military plane and a few days later the

Pitstop Ploughshares Five had a go at the same plane after it had been repaired.

World Airways pulled out and repression from the police and media went up well

more than a notch. The terms of Mary Kelly’s bail was to ban her from Clare,

and the five were to spend several weeks in prison, only being released with

punitive bail conditions – including having to sign on every day with the

police. The media smear campaign – which is basically the psychological

warfare wing of the police – also went into action. Sections of the anti-war

movement –such as the NGO peace alliance (who had just organised a 800 strong

demo in Shannon) and the Green Party – who were pro-smashing warplanes one

minute and not the next, sought to distance themselves from these actions.

| And the troops went in with

armoured cars and guns; they would have had tanks only the Irish army

doesn’t have any. This was half a publicity stunt, half a cost-cutting

exercise as soldiers don’t have the power of arrest but are paid much

less than cops. The Star’s headline "Will They Shoot on Sight"

must have given hard-ons to many in the US Embassy. That was the point:

intimidate the ‘citizens’, reassure those whom the ‘public servants’

really serve. Two weeks later we were to get a lesson in the reality of

"democracy". F15: over 100,000 on the streets of Dublin, opinion

polls showed massive opposition to the Government’s support for the

Anglo-American war effort. Many of us had argued that marches around city

centres had no impact on state policy. |

|

And the troops went in with armoured cars and guns; they

would have had tanks only the Irish army doesn’t have any. This was half a

publicity stunt, half a cost-cutting exercise as soldiers don’t have the power

of arrest but are paid much less than cops. The Star’s headline "Will

They Shoot on Sight" must have given hard-ons to many in the US Embassy.

That was the point: intimidate the ‘citizens’, reassure those whom the ‘public

servants’ really serve. Two weeks later we were to get a lesson in the reality

of "democracy". F15: over 100,000 on the streets of Dublin, opinion

polls showed massive opposition to the Government’s support for the

Anglo-American war effort. Many of us had argued that marches around city

centres had no impact on state policy. We pointed out that the really huge

demonstrations which had taken place in London and Glasgow had not changed

British Government policy which was still dictated from Washington and were

accused of being negative. Well here was the proof in Ireland that we were right

– we marched, but nothing changed. Demonstrations like this can be useful, as

a morale boost, as a way of getting more people involved. I helped organise four

buses to F15 and two local protests around that time. But a strategy of marching

and marching alone will do nothing. You couldn’t miss the truth of that when

in the face of the biggest demo in Dublin in years the state didn’t change it’s

actions one iota. Unfortunately this truth missed self professed

"revolutionary Marxists" (like why have a revolution if lobbying

works!??!!) and republicans (hey couldn’t you have had a protest march instead

of ‘800 years of struggle’?) by a couple of hundred miles.

It would be nice to have a real positive article but how can

we write about the March 1st action without mentioning the massive

hostility shown by the Left towards it? March 1st was first discussed

during the January 18th demo, developed in local meetings after soon

after was put forward to the leadership of the Irish Anti-War Movement (IAWM) as

a day on non-violent direct action. We emphasise the word leadership because

much of the membership of the IAWM had no awareness of our approach. That

leadership’s reaction was to call a protest march for the same date, then to

claim that nasty anarchos were hi-jacking their event. In the week

running up to the March 1st Action, two charter companies carrying

American troops through Shannon pulled out, citing "security threats".

World Airways having already pulled out, according to media reports, this left

one charter company hired by the American military still using Shannon airport,

as well as direct military flights. One big push might have done it.

Instead, the Labour Party, the Green Party and Sinn Fein all

pulled out of the day without consulting the rank and file, though to their

credit, individual Labour Party and Green Party people refused to follow the

diktat of their leaders. The Socialist Party and Socialist Worker’s Party

marched in a separate contingent which ignored the attempted direct action and

meandered up to the terminal. The Green Party had their national conference 30

minutes up the road where Shannon was high on the agenda for discussion!!!!!

Some people had genuine problems with a ‘day of action’ but when a political

party which (still!) has an armed wing starts waffling about the need for ‘peaceful

protest’, y’know this is for party political reasons not a matter of

principle. These parties want to appear radical to hoover up radical youth, yet

respectable enough to win votes, forge electoral alliances or earn union

funding. They invented reasons not to support the March 1st action

and denounced it in the mass media. For example: ‘it won’t be a family day

out’. Aye, and Trotsky went down in history for running a crèche during the

storming of the Winter Palace. Or: ‘It’s premature’. Sure, after the fall

of Baghdad would have been a better time. There is no evidence that public

opinion and protest marches altered the situation and clear-cut evidence that

direct action at Shannon changed things. If you don’t believe me, ask the

airlines why they pulled out of Shannon or Jane Fort, acting head of the U.S.

embassy in Dublin. In the Sunday papers following March 1st, she

admitted that direct action had caused "difficulty", had prompted the

airlines to review their position and the movement’s tactics had been

"really threatening". This from the representative of a regime guilty

of mass murder, stating clearly that we had got them over a barrel and on the

run. You could play by the system’s rules, do only what you are permitted to

do, and Jane Fort will probably love you, there will be no controversy, you’ll

have a nice media image, no political backlash……and you’ll get absolutely

nowhere. Imagine what a unified mass non-violent direct action mobilisation in

Shannon on March 1st could have done. Following March 1st,

the movement went into reverse. Day X reaction didn’t keep the pressure on

Shannon and two of the further demos there either massively policed by the boys

in blue or kept under control by the political parties.

Direct Action is not another way of saying militancy, it

means going and sorting a problem yourself, as opposed to indirect action -

asking someone else to do it by lobbying or voting or whatever. Direct action’s

purpose is to have an effect, to directly sort out the problem. The diverse

actions at Shannon, by creating a ‘security threat’, led to the charter

companies pulling out. Shannon was being demilitarised as a result of direct

action. Now there’s all kinds of ‘direct action’. The successful

penetration of security at Hillsborough during the Bush-Blair summit? The

blockade of the Dail? Here in Galway we marched into a Fianna Fail office, and

likewise in many other places the focus was on the politicians. But where was

the end product? Many of these events had the form of direct action but the

content of protest lobbying. ‘Put pressure on the politicians’, start with

letter writing, get progressively frustrated through protest marching until you’re

throwing paint at the pricks. But in the end the focus is still on politicians

who will not listen. After Day X, the dominant form of action was…. wait for

it…marching. This can be a cul de sac. You come to a march in Dublin, then

another and another. As they have no noticeable effect do you keep coming? Or do

you just become more cynical and disillusioned? We need an effective strategy.

We need to fight where we can win because that builds confidence and overcomes

apathy. The point of direct action is to build up a general climate of

confidence and culture of resistance through winning and most importantly

through winning by our own efforts.

The conservative left’s campaign against direct action

served to facilitate state repression. People arrested in October started to get

their summons and more people were arrested and charged on March 1st.

House raids, arrests and riots cops appeared on the horizon. Blanket policing

prevented a march from even getting into the airport grounds. The numbers of

cops at Shannon station increased massively: last year there were 234 cops in

Clare with only 30 in Shannon. Now there are 140 in Shannon alone. Many

activists have been banned from Clare despite it being unconstitutional

according to a High Court judge. Even so, the state has not thrown a ring of

steel around an impenetrable citadel: on Good Friday last, the Catholic Worker

spud-planting division went walkabout through the airport grounds and built a

shrine. The state has mobilised sufficient numbers of police to match the

numbers those networks up for mass direct action can produce. They have also

know that the only mass direct action they were going to see from large sections

of the anti-war movement will be rhetorical. Charter companies have returned,

and others have come to replace the ones that haven’t. To prevent further

demobilisation, defendant/prisoner support is crucial. Its effectiveness (or

lack of it) will inhibit or facilitate further action or further repression. All

of the fines and legal costs arising out of the March 1st action, and

most of the costs from October 1st,, have been met by support

networks.

From a libertarian perspective the point of direct action is

that people winning small victories through direct action are empowered – a

culture of resistance is built up. This is an essential short term goal for all

who dream of a free society without hierarchy and bureaucracy. You cannot change

social relationships by legislation but only through a mass movement of people

shaping their own destinies. Only an empowered people can do this. We need to

create and support forms of direct action that are most accessible to all

people. We don’t need a specialised activist elite – unless we wish to

reproduce the hierarchy and alienation of capitalist society. We need mass

participation.

We are faced with a conundrum. Direct action (which only a

small minority can/will take part in) or ineffective protesting? Are those our

only options? It looks like it, if it is currently beyond our capacities to

mobilise sufficient numbers for mass direct action. However there is a way out.

That way out leads through the soft underbelly of USAF Shannon, the corporations

which operate the airport. Top Oil re-fuels the warplanes but it may also have

put the petrol in your car or the oil in your central heating. As a pretty small

indigenous company, with just over a hundred filling stations and some local

distributors in a very competitive market, it is susceptible to a consumer

boycott, which would have an immediate and direct effect.

We can establish a spectrum of resistance ranging from

boycotts to mass trespasses to hammering planes, in which everyone can play a

direct part in the de-militarisation process. All of us can participate

directly, on our own initiative, at whatever suits us. This strategy also

applies to other issues and arenas of struggle. Our main goal should be on

seeking ways to have an impact and empower people through mass

participation. In regard to Shannon, obviously the heady days of the spring of

2003 are over. Time to pack up and go home? I think not. The planespotters down

at the airport report no appreciable reduction in military traffic – hardly

surprising when you consider that troop numbers in Iraq have not be reduced. The

war may not continue on Sky News but it does on the ground. Similar arguments

were heard in the aftermath of Afghanistan, that is: no war equals no anti-war

movement. But the war is still going on and it is being waged as much by local

businesses like Top Oil as it is by the US Marines and fedayeen. Something

like the Top Oil Boycott Campaign can incorporate action – hurting the company’s

sales figures and propaganda – keeping Shannon and the war in the popular

consciousness by being out there on the forecourt.

The pictures used in this article come from the Workers

Solidarity Movement site: http://struggle.ws/wsm.html.

There are many more to view on their site.

Back to top of page.

The

Anti-War Movement in the North East

| Though the war in Iraq is still

being conducted at a low level, memories of the anti-war movement seem

very faint. Yet, for a few brief weeks in spring, a highly significant

movement helped send perhaps 2 million people to demonstrate in London and

a further 100,00 in Glasgow. The opposition to Blair’s invasion of Iraq

also appeared in towns and cities all over the country and was sustained

for several weeks before the war was finally declared ended. As everywhere

else, the north east of England experienced some inspiring moments in this

campaign and the anti-war movement there, like elsewhere, provides both

inspiration and lessons for anarchists.

The Tyne and Wear Stop the War Coalition

was set up in the aftermath of the September 11 destruction of the World

Trade Centre, it being obvious from early on that the US would respond

with aggression and violence, and that Britain would support this

stance.But things did not really take off until relatively recently: the

attack on Afghanistan stepped up the tempo, which reached fever pitch with

the build-up to the attack on Iraq; an attack everyone instinctively knew

had been decided on months before.

Before the war started, one of the best

things that happened was an occupation of the Labour Party national

recruitment office in North Shields on 7 February. Two people pretended to

want to join the party and the rest covered the camera on the door and ran

in. A group went upstairs to try and get a banner out of the window while

others stayed on the ground floor. A third group stayed outside. |

|

The staff were a bit radgy at

first, the receptionist trying to stop protesters from putting their banner out

the window by saying the window had to be kept shut for the central heating! The

cops came but realised they could do nothing to remove the occupiers, so they

stayed until the media turned up. The staff inside were pretty aggressive but

they calmed down and a few occupiers ended up talking to the staff about why

they were doing it. Many of the staff seemed to think that they were ‘non-political’,

and that the target was not legitimate (odd as it was national Labour Party

office and most of the workers there were Labour Party members). After about two

hours inside the occupiers agreed to leave, to a paparazzi-like reception from

the media. All in all it went pretty well. Though it would have been better if

the occupiers had made a bit more of a nuisance of themselves, it got some good

media coverage (both ITV and BBC cameras showed up, as did three radio station

and two newspapers) and there was a national Labour organiser up from London

there at the time, so presumably the message got back to London at least…

But this was a relatively small

group of people. Though there were others demos and stunts, the really

interesting stuff happened on the day the war started. This is a report written

at the time:

The first day of war in Iraq saw

some of the largest and most militant activity that Newcastle has experienced in

recent times. Events began at 8 am at the Haymarket. A crowd of 80-odd that had

gathered moved into the road and blocked traffic for forty-five minutes. Some

gave out leaflets but most sat and chanted in the road. A banner was hung off a

nearby church. There weren’t as many of the usual suspects, due to some

uncertainty regarding when the war had actually started. Fortunately there was a

large group of school kids and sixth-formers from Heaton. Identified by their

pink sashes, they were the most ‘up for it’ and they made it happen in the

morning.

Eventually, the crowd moved on. Some

went to work but the kids weren’t finished yet. They marched to the Monument

and spent half an hour chalking anti-war slogans all over the area. Dissatisfied

with that, the kids moved off again… to the Metro. The cops had heard where

they were going and accompanied them to the Metro doors. For some reason they

didn’t follow the group to Gateshead, where they made straight for the Tyne

Bridge. Stopping traffic on the Tyne Bridge was child’s play. No coppers

showed for ages. Initially sat on the Gateshead side, people decided to take the

middle of the bridge. As they moved off, a copper finally caught up. He drove

past, stopped and tried to make people stop, but everyone just walked past him.

Nonplussed by this, he got out and grabbed the first person he saw. Then things

started getting a bit hairy. Whilst the copper was tussling with his arrestee,

several radgies had got out of their cars and were looking like they were gonna

kick off. Then several cops vans showed and the fun was over.

The group then marched back into

Newcastle, accompanied by police vans the whole way. At lunchtime, it met up

with the main march and again stopped traffic at the Haymarket. The final event

of the day came at a 6pm anti-war vigil. Addressed by the usual (and far too

many) suspects, it looked like the crowd of perhaps 1,000 was going to end up

bored to death. Despite this, a large group (several hundred) hung about and

then marched up to the Haymarket and again stopped traffic by sitting in the

road. [Eventually] the crowd ran across the park by the church and sat in the

road back where they’d just been; the cops didn’t have a clue what to do.

With ten years if political activity

in the city, I had never seen anything like it. A large crowd, mostly people

under 18, intent on causing disruption and testing the state’s means of

control. It seemed like the cops would never shift people, but then the church

stepped in. A vicar appointed himself police liaison and informed the crowd that

the police had identified ringleaders and would be making arrests if they didn’.

Instantly, a few people stood up saying ‘I’m a ringleader, arrest me’…

and there followed one of those incredible ‘I am Spartacus’ moments as

everyone stood up shouting the same thing. Yet, it was clear that something had

been killed. Maybe most weren’t up for risking arrest, but there is absolutely

no excuse for doing the police’s dirty work for them, regardless of your

motives. (The clergyman in question had been heard to say in the morning demo

that people shouldn’t sit in the road as they’d look like a bunch of

anarchists, so it was clear, and predictable, where his sentiments lay).

The coup de grace was delivered by a

representative of a similar organisation. The SWP regional organiser then

announced that the demo was over and everyone should go to the next one. The way

in which such a high level of solidarity, spontaneity and militancy was

effectively killed by people who were meant to be supporters of the cause was

nothing short of a disgrace. It definitely did not need to end that way.

Yet, this incredible day, did not

herald the start of an even larger and more militant campaign of direct action.

There was another rally-cum-march on the Saturday after war started but the

police refused to let the crowd march up Northumberland street as it was busy

with shoppers. They cordoned it off but people went through various shops and

the march kind of happened anyway. It dispersed after a ‘vigil’ at the war

memorial and there weren’t enough people to do a sit-down on the road again.

Most of the kids weren’t there, and they were the ones who had made it so

successful the previous Thursday. An attempt by a few people to sit in the road

ended in predictable failure as angry taxi drivers jumped out of their cars. It

was also a Newcastle home match and a lot of the fans were pretty abusive. Since

the war actually started a polarisation had occurred, as might have been

expected.

After that relative failure I still

thought that the success of the first day’s action could be repeated or even

bettered but, unfortunately, I was mistaken. The subsequent Thursday and

Saturday meetings began to decline in size and militancy. By May Day things had

reached a real low. It was the most depressing May Day march I can remember (no

mean feat given previous marches’ ability to induce feelings of total

despair). It was pathetic and embarrassing marching through town. Did the shite

way the first night’s actions were killed-off put people off doing anything

similar? What is certain is we didn’t see that same level of militancy again.

The experience of that night left a bitter taste in my mouth and, I imagine, in

that of many others.

For an all-too-brief moment we had

glimpsed something special in Newcastle. The political impact on those who

became politically engaged for the first time is something that can and will

last. In the north east one of the most important features of the anti-war

actions was that they were supported and often inspired by people who had not

taken direct action before. It was great to see, for example, a load of kids

running onto the ‘blinking eye’ bridge and locking on, when we’d heard

that a naval training vessel was due on the Tyne (and consequently needed the

bridge to be raised). It was the kids of Heaton that took the Tyne Bridge and

the youth of all Tyneside seemed to be at the mass road blockade in the evening.

The youth gave the demos a lot of energy and inspiration, and they were up for a

lot more than just marching and chanting slogans. Another positive development

has been a lot of young people coming into contact with anarchist ideas and

setting up groups. Now there are Anarchist Youth Network people in places like

rural and very Tory Hexham, and other groups elsewhere who are now interested in

anarchist ideas.

The internal politics of the Stop

the War Coalition was predictably messy. A coalition of peace activists,

liberals, Greens, lefties of almost all 57 varieties, anarchists, hippies, other

ne’er-do-wells, some old Labour people (I think) and other assorted

odds-and-ends, it was always likely to end in tears. It often did. And when push

came to shove it almost always seemed to be the SWP and a few hangers-on versus

the rest. A group outside of the STWC did the Labour Party occupation and it got

slagged by some at the following STWC meeting. The SWPers accused the occupiers

of being "super heroes", "elitist", and "petit

bourgeois" etc. (the same old unoriginal and frankly meaningless platitudes

you’d expect). The SWP didn’t like it but it was being left out that really

rankled especially as it appeared to be one of the more effective things done in

the region.

Then there was the repeated SWP

attempts to push through their re-organisation idea. The effect of this would

have been to create a ‘committee’ with a handful of ‘elected’ (read SWP-appointed)

people who would make all the decisions and co-ordinate the whole regional

campaign. It seems that it’s more democratic to have this committee then it is

for anyone who wants to get involved just coming along and having their input.

One of the most hilarious aspects of it all was the SWP claim to represent more

people and therefore deserve more voting power/influence over what went on. If

an SWP member is a trade union branch secretary, ergo he or she represents all

the people who are in that branch in whatever meeting they happen to be taking

part in. The truth is, like the rest of us, they represent themselves, their

party and no one else. Anyway, they argued that at present the STWC was not

working efficiently in the region and that it needed co-ordination by this

committee. Bar one or two others, like a student who thought that a ‘command

structure’ [!] was an essential part of any organisation, the rest argued that

it worked well enough as it was: the problems that did arise could be sorted out

as and when necessary; the committee idea meant putting control into the hands

of a few people at the expense of everyone who wasn’t on the committee;

specific events could, as was already happening, be organised by sub-groups of

those interested. The first time the committee idea came up, it was not

decisively dealt with, though it was obviously unpopular outside the ranks of

the SWP.

Failing to get what they wanted

inside the STWC, they attempted to establish another organisation they could

control; a north east ‘people’s parliament’ briefly found its way into an

uncaring world. It soon vanished and another attempt at getting the committee

adopted was made. The same arguments were had, that it was about control not

democracy or organisation, that we should be doing things not wasting time

arguing about how we should be doing things. After heated and at times very

comic debate, it was voted down. The STWC was operating in a relatively ‘anarchist’

manner. With no formal hierarchy, it was characterised by openness, equality and

democracy. Of course, it could have been better, but most of the problems were

down to people not using some initiative and not communicating. Most of the

complaints came from SWP members, as if they were deliberately trying to show

that the structure didn’t work. The SWP fervently believes you can’t

organise without people telling you what to do. They were going to try and

impose their ‘top-down’ model and show us (a) we needed leaders and (b) they

were the best people for the job. Though a committee would stifle initiative and

creativity and disempower people who were wanting to do stuff, it would have

given control to the SWP.

There are many lessons that need to

be understood or things that require thinking about by anarchists, arising from

the anti-war campaign and its activities:

(1) Spontaneity, often from people

new to ‘political activity’, can be a very effective tool if you want to

keep the police on their toes and cause maximum disruption. There is no need

for marshalling, corralling and generally being controlled a la SWP.

(2) If the SWP or other

authoritarian groups try and control direct action, then ways are needed to

prevent what happened to end the demo on the first day of war. In the

immediate aftermath of that debacle, some argued that loud-hailers should not

be allowed on marches. It’s not really the loud-hailers, but the people

using them who cause the problem. Ways and means need to be found of stopping

would-be leaders from attempting to assert a dubious authority on proceedings,

but without appearing like other would-be leaders. Someone getting up and

using the loudhailer to say ‘sit tight and ignore the guy telling you to go

home’ is in some ways being guilty of the same thing. We need to find ways

of combating those who elect themselves to sell us out. Maybe the kids, who

were the main inspiration of the days’ events, will learn to deal with this

in the future... Answers on a postcard, please.

(3) It was clear that the old

formula of ‘big public meeting, with twenty-five different speakers’ is of

very limited use. Once everyone who likes the sound of their own voice too

much has had a go, there often seemed less people left in the crowd than on

the platform. Those remaining invariably wore the expression of people who had

lost the will to live. Events in Newcastle showed people wanted to do

something, and we should think about ways in which we can make all this stuff

more participatory for the people involved and more disruptive to the powers

that be. They’ll happily have people boring other people at the Monument for

as long as we can bear it.

(4) Though the STWC has people in

it who we’d never normally choose to work with, it is important that

anarchists involve themselves in such organisations: to get anarchist

arguments about organisation across and to attempt to frustrate authoritarian

ideas. Some people will come across anarchist ideas for the first time and

many will be influenced by them rather than go with the SWP. Sadly, even after

having seen how the SWP operated at close hand, some still chose to join them

in the aftermath of war. Due to all the Stop the War activity, people who had

shelved a pre-war idea for a conference to establish a new direct action

group. The new group eventually emerged too late to prevent at least some of

the anti-war people getting mopped-up by the SWP. Learn from our mistakes.

(5) Having people you know and

trust with hand-held video cameras when doing some kinds of activity is very

useful. A lad was arrested on the Tyne Bridge for obstructing and was also

charged with assaulting a police officer. He didn’t do it, needless-to-say,

and we have a video of the whole arrest that shows quite clearly that he didn’t.

The case was recently adjourned and apparently the copper started saying he

was ill and couldn’t attend court when told we had a video as part of the

defence. The case was adjourned and it is likely that the assault charges will

be dropped thanks to the video (which the copper incidentally tried to

illegally snatch off the lad operating it on the day). Another good aspect of

the presence of ‘youth’ at these demos was the police’s obvious

uncertainty about whether to arrest them or not. They would obviously have

preferred some ageing hippies to rough-up instead.

(6) The lad in the Tyne Bridge

arrest had support with his case. This did not happen in an earlier case when

a lad was arrested and manhandled by a load of coppers for writing ‘Justice

Not Vengeance’ on the Monument. A lot of the people said they’d not go to

any more rallies as he’d been ‘violent’ etc. He subsequently got very

little support from coalition members and was found guilty of criminal damage

and fined £50, the cost, apparently, of removing the chalk. Though the STWC

did pay his costs (it needed to do something with all the money it’d been

accumulating, after all), he didn’t want to involve himself in it further;

understandable. You have to be prepared for this kind of thing when working in

such a wide and diverse kind of coalition.

To sum up, anarchists should be in

STWCs and arguing an anarchist case. Fight the authoritarians as much as

possible and try to show by practical example that anarchist methods are the

most effective way of organising. Those new to political activity will hopefully

learn something from anarchists, and we, in turn, will definitely learn from and

be inspired by, them.

Back to top of

page.

Interview

with Nika

On June 19th we had the opportunity to

interview Neka, a representative of the Argentinian autonomous movement. She is

a member of the piqueteros, the movement of the unemployed, so called from the

Argentinian word for blockade.

Though they are best known for direct action, they carry out

much wider projects, developing neighbourhood networks, education and health

intiatives and microcompanies, self organised workshops in which the unemployed

make first what they need then products for sale to get some income. This is

especially important since there has been no dole or benefits in Argentina until

recently. Even the very limited dole came as a result of the direct action of

the piqueteros.

|

Argentina made headlines a year and a half ago, due to the collapse of the

economy and political institutionals. Millions of Argentinians lost their

savings and money in December 2001 when the economic policies implemented at the

orders of the IMF and World Bank and others crashed; this certainly increased

resistance. But the struggle of those affected by harsh living conditions has

been a constant for a long time. The state continues to decine due to a lack of

legitimacy and resources, abandoning responsibility for health and social

services for instance. This makes self-organisation a necesssity for most

Argentinians, who need to build their own structures so they can go on with

their every day lives.

This has provoked a debate about the role

of the state. Though most of the time services are delegated to it, there’s

no need to do so. Self-organised workers can do the work, providing

health, education and other services to higher standards.

|

|

After all it’s us, the workers, who do the real work

and not state bureaucrats. But while the state collapses and retreats from a lot

of its supposed duties, it has never had any problem to keep up, or even

increase, the level of repression, thus disclosing its real nature and

priorities. Even in the days of December 2001, when governments were made and

unmade in a matter of days, if not hours, the only fully working state

organisation was the riot police, which killed many demonstrators.

It’s difficult to think of any possible solution for the

Argentinian crisis in the foreseeable future, especially via capitalism. The

fact that international organisations such as the World Bank or the WTO are

demanding more of the same policies that led to the crash, and that

international banks are pressing for debts to be repaid, is not helping at all.

Through these last years, only the will of the people to resist, finding new

ways of social organisation, has allowed them to keep their lives going on. Even

if it had a lot of problems and set-backs, as we would expect when someone is

exploring new ways, it was a very important and kept hospitals, schools and

factories open. Now the bosses and the state are coming back, as if nothing had

happened, to reclaim the companies or areas that they left when the crisis

struck. Their only argument for this is coming from the barrel of a gun. There’s

still a future of struggle for the Argentinian people ahead. We can only hope

that we can support and help them.

Interview with Neka, representative of the Autonomous

Argentinian Movement.

Could you explain to us who are the piqueteros, how they

are organised and how they first appeared?

Let me introduce myself. I’m Neka and I am a member of the

MTD Solano. We are part of a coordination of different movements called MTD

Aníbal Verón. We began to get organised at the end of 1997, mainly out of

meetings and assemblies in the neighbourhoods, as we began to be badly hit by

unemployment. That was our starting point.

These assemblies and meetings, did they begin

spontaneously, or were they an initiative taken by some existing political

group?

No. Most of us had met each other through the every day

reality of the neighbourhood, as we were engaged in different projects. For

example, I was part of a team working on health issues in our barrio. We had

been in touch, there was a bond between us. And there were also some compañeros

who had been involved in other projects in the area. When we first decided to

get together and discuss the problems brought by unemployment, most of us had a

deep and sound knowledge of our barrio.

So there was a previous experience of organising at a

local level?

Yes. The area where I come from, San Francisco Solano, is a

town of 80,000 people. All the barrios are the products of asentamientos, the

squatting of land to solve the housing problem. That started in the 80s, so

there is a history of struggle, very strong and hard in this area. We had

already been doing together different actions, assessing different ways of

getting organised and of solving the main problems in life.

The piqueteros are represented all over Argentina...

Yes. It’s a very diverse movement. This word, piquetero, we

never branded ourselves like that. It started being used by the media, that is

the state, in a disrespectful and pejorative way, to imply that we were

criminals, subversive elements. When we began to get organised there was still a

middle class, which doesn’t exist today any more, and it was really hopeful,

waiting to see what capitalism and neoliberalism had to offer. So when we began

to blockade roads and occupy public buildings, it was a very shocking thing.

Since then the social and political situation in the country has affected wider

sections of the population. They have deeply felt the consequences and awakened

from the golden dream of capitalism, the dream of progress for some through the

wage labour, the exploitation of the rest; comfort, consumerism...

Was there a particular time at which you decide to start

with these actions, road blockades, etc? Was it from the start, or was there

first a process of radicalisation that you went through?

There’s not a single unified movement, there are lots of

different ones and each one of them has its own way of organising. For some, the

piquete, the blockade on the road, is the most important stuff. They look for a

more media-focused way of building up the movement or the political party. For

us the main thing is behind the blockade. As the MTD Solano we say that the road

blockade or squatting a public building is only a means, and the most important

things are happening in the barrio, at the assemblies, through the collective

way of making decissions. Before we do any action we discuss a lot in the

meetings why we are going to do it. What is the meaning, for example, of

blockading a factory or a mill, places where the raw materials that we need to

produce or to feed ourselves are kept. Before we squat a Carrefour, the

multinational supermarket, we discuss the meaning of this capital concentration,

as well as why the food is concentrated there, and not where it should be.

Direct action and project construction in our barrio come together; we construct

every day in our neighbourhood what we demand in the street.

What’s the impact of all these projects in the lifes of

those taking part in them? Has it come together with an evolution in political

ideas, in the nature of demands made?

I think there was a very important break with traditional

politics and political issues, and it is precisely related to all this. We’ve

been through a lot of different organisational practices, lots of experiences

and what we’ve finally learnt is that we can build up better projects without

leaders. We don´t need any one speaking on our behalf, we all can be voices and

express every single thing. They’re our problems and its our decisions to

solve them. The fact that we have education, popular education, as a central

axis of our project, allowed us to open space for discussion and thought, to

start building up new social relations, to deeply know each other, so we could

feel we are all part of everything we are building. Getting back our dignity

depends only on ourselves and not on a boss or anyone else imposing on us a way

to live.

What you have said about popular education, is there any

practical project on that, or do you mean more like sharing the experience of

social construction?

No. As we understand society it is based upon domination

relationships, so anything coming from its institutions will be based on this

same principle of domination. Education is education for domination. Same as the

family. So when we propose social change we have to begin at the beginning and

devise new relationships. I think this is the challenge. When we decided that we

had to produce our own foods, to struggle against the monoply of food production

we understood that new relantioships are born of this practice, through

discussing all these issues. And also horizontality and autonomy, and all the

things that are not abstract ideas or theories, but a practical issue and a

process. Popular education, the dynamics of the meetings and assemblies, are all

part of the effort to change these relationships.

What are the relations of the movement with more

traditional forms of the left? Have they tried to use you to achieve their

goals?

I don’t know how it is in other places, but that’s a

usual thing in Argentina. When there is something interesting happening any

where, the parties first either criticise or try to manipulate it. So there’s

not only the need to fight against the right, but also against attitudes and

deformations from the left. We understand that there are areas in which we can

work together, like against the debt or repression. This causes problems for

those of us who believe we need to build the movement up from autonomy as much

as for those who believe in a more classical way. But we think from a very

different logic and the new society we can think of is very different from

theirs. I think they’ll have to learn. They’ve gone through a lot of

setbacks and they’ll finally learn that there are ways that don’t work out,

as they became as authoritarian as all that they criticise.

Have you ever had any problems to keep the assemblies

independent?

A lot. We are all the time being criticised, and there are

always attempts to manipulate and infiltrate us. We are all the time discussing

how to take care, not only on a personal level, but also of the construction of

our projects.

Could you tell as a bit of how all this is practically

implemented, how the assemblies work and how they are co-ordinated between each

other?

There are different levels of co-ordination. There are seven

barrios in the MTD Solano and on certain projects they work together, like on

health, education, productivity or economic projects. Through delegates we put

together initiatives in these areas but also plans for the struggle and more.

These delegates meet once a week, from different places and areas and they

represent the decisions made in their assemblies. Also the MTD Solano itself has

its own delegates, who meet with others and coordinate all this effort and all

this experience through the MTD Aníbal Verón. Some times they may be leaders

or decision makers. In our case the delegations are taken in turns and can be

recalled. If they don’t voice the decision made by the assembly they can be

recalled.

Was all this co-ordination at a wider level this way from

a start or has it evolved and gone through changes? Was there a discussion on

how to have it put in place?

I think it was the needs of the movement at different times

which made us say to ourselves: OK, lets stop discussing political differences

and strategies and lets co-ordinate a bit of struggle against the issues hitting

us hard, such as the repression. In less than a year we’ve had three

compañeros killed in the MTD Aníbal Verón. This week makes a year since the

Avellaneda massacre, in which two of them were assasinated. This repression made

us stop and think that we had to coordinate a struggle against it. Also the

affair of the corralito, the expropiation by the state of the savings of the

people, we could see it was not only affecting those deprived of their savings

but also the every day life of the whole country. I think that reality itself

has imposed different levels of coordination on us.

Has there been an evolution in the level of the repression

that you’ve had to confront?

I think that the repression in Argentina has never ended, the

dictatorship has never ended. There’s been a change in the nature of

repression, which is now much more subtle and much more dangerous, such as

different ways of social control and the means they employ to control the social

movements. I think that the state is repression, that the essence of the system

is criminal. When the state leaves millions homeless, without any benefits or

health service, that is repression. When kids are starving to death every day,

dying of malnutrition or bad health, that is repression. These policies are

repression, economics is represion. Of course this comes along with batoning and

shooting those demanding in the streets an end to it, asking for what we have

right to. An interesting side of repression lately, is trying to have all the

popular struggles become part of the institutional process, searching for every

mean to buy the leaders. That’s why we don’t have leaders, because in the

end they always agree to something the people doesn´t want, something the

assemblies don’t want. This is the more subtle way, and through propaganda,

criminalisation, through new laws and organised groups. They are taking

advantage of the situation to organise alternative groups in the barrios, paying

youngsters from the area to work with the police and the state, killing

militants, chasing people down. There have been more than 300 different cases of

faked robberies involving shootings where some militant is killed. This is

organised by the police itself. For us it’s all part of the same military

dictatorship that ruled in the 70s, only in a different fashion, with the mask

of democracy.

So we can say that every state, either a dictatorship or a

democracy, always follows the same pattern, that of repressing social movements.

There´s a change in the form, in the shape, but the essence

remains the same. It´s a matter of detail.

It seems to be a situation of class exploitation in both

forms of government, and the role of the state is to ensure and protect the

privileges of the rulers, the rich and powerful.

Of course. As I see it the true democracy is when we all have

a posibility of saying what we want, of choosing how we want to live, without it

being impossed on us. As long as these domination relationships exists, as long

as there is an imposition of how to do things, there cannot be any democracy, no

matter how popular a government is.

Do you also keep in touch with other types of social

movement, like the workers running the factories, or any other?

Yeah. The network of squatted factories is very diverse as

well. There are about 200 of these and a lot of different proposals on how to

run and defend them. But there is also a network of co-ordination between them

the squatted factories, the assemblies and the piqueteros. Recently there’s a

strong co-ordination with other squatting groups as well, such as teachers,

doctors, etc. It’s a very interesting process.

Do you think that your movement served as a model for other

groups that began to get organised after theDecember 2001 crisis?

I think so, I think it’s been useful even though we don’t

believe it’s right to become a model or create a dogma, nothing like that. But

I think there are experiences that multiply themselves and get diversified,

which is very interesting. We’re always having comrades from other places

coming along to visit, to stay with us for a while, work and see, and they’re

very happy with it.

Do you co-ordinate with anarchist groups? Are they simply

organised as members of the assemblies?

No, there were moments in Argentina of a very strong

anarchist struggle, such as those of the so-called tragic week or the Patagonia

Rebelde, when the first unions in the Patagonia were established. This influence

is very strong in areas of the movement such as education, organisation. We are

also interested in the Spanish Civil War and its different experiences. There

are some compañeros at the MTD Solano who come from the anarchist struggle. We

have big similarities with the historical way of building up an organisation.

But nowadays in Argentina we don´t keep any big relationship. We do with

individuals, but not with any anarchist organisation.

What do you think the role of globalisation, and

international capitalism, has been in the crisis that Argentina is going

through?

I think that even though national economic institutions and

the state have responsibility for everything happening, I still think that the

pressure has been on a global basis, that the interests of big capital have out

this pressure on. They have effects in countries like Argentina but also on

everything happening in Africa, in Asia, and on some countries of Europe itself.

It’s a conscious policy, planned and executed by the likes of the

International Monetary Fund, the big corporations.

How do you see the attempts to create an oposition to this

neoliberalist project by building up an nternational anti-globalisation

movement?

We take part in a lot of forums, for instance the Porte

Allegre summit, meeting people from all over the world. But we also meet many

others at a regional or continental level. We find them very interesting spaces,

but we also think that there’s a point in stressing the issue of co-ordinating

only that which can be constructed or practised. There’s a risk of having only

speeches, agreements, theories and when we come back home, nothing happens. The

system is preying on and living in our spaces, in our every day life. It gives

us an education to make us obey, it imposes the way our clothes are, and where

we have to live. You and I cannot choose the place, the house or the barrio

where we want to live. I think that the struggle against this taming, this

domestication or discipline that we all receive so make us obey the system, that’s

what we have to co-ordinate afterwards.

Try to get back the decision making on our own lifes.

I think so, yeah.

Talking about practical stuff, what do you think we could do

from here, Europe, to support the struggling people of Argentina?

Where we get strength and hope is from meeting other

struggling people, or those who are doing things in their areas, proposing a new

way of life. There’s also the sharing of resources. Usually here, as well as

in Spain or Italy, there’s more resources, things that we lack. Support, and

sharing things as much as we can, I think that’s a very important issue. There’s

also the repression. I thing it’s been reduced thanks to world wide

demonstrations, even when it was very strong. Though we don’t expect much from

international organisations, protests and demonstrations in front of them, of

embassies and so on does call attention to our situation.

If we look into the future, do you think there’s any

solution for the crisis in Argentina within capitalism or would any solution

have to go through a radical redefinition of everything?

At the moment in Argentina we have a big void due to the lack

of legitimacy that the state has had lately. But at the same time the system is

very enduring and goes on creating conditions for it to survive and thrive. This

is happening with the new government but it doesn´t mean that the right

solution is being applied, for us. There´s no valid answer from any reform or

reproduction of what we had before.

Q.- Can this void of power that state crisis has brought

along be filled by a network of all the struggling sectors? Do you think that

such a coordination could be the embryo of a new society , organised in a

different way?

We, at least, are not thinking with the same logic that we

are used to. I believe it is possible to imagine a different kind of society. We

at MTD Solano don´t have any faith in a revolution employing the same methods

of the bourgeoisie to govern. There must be a different logic.

Yeah, could spreading this way of organising, according to

these different logics, could it take over the state, so at the end you get a

network of assemblies managing the every day life of the workers?

Yeah, I think that would be the logical way, wouldn’t it?

Because that’s the only way every one can take a decision on what affects

them.

Finally, how do you think that this is going to evolve? The

movement itself, also the social and economic situation in Argentina, what do

you think is going to happen, and what would you like to happen?

I don’t think the conditions are ripe for a popular

government, no matter how much they want it. I think that, for a while, they´ll

use some mechanism to create some social consensus, to gain the support they

need to stay in power. But at some point it’s going to kick off again. They

are using a lot of tools to create hope in the people, as they did when they

brought Lula, Chavez, Castro. But all this, at least as we see it in the MTD

Solano, is simply a mask to fool us. In fact, I think that this government is

already having a lot of problems carrying on. We don’t expect any important

change, any radical one, of any good for the people. The challenges, at least

for us, are to go on getting strong in the barrios, making a sound organisation,

analysing the new situations in depth and fighting creatively the situations

that arise, and don’t let ourselves become dogmatic, either.

So a future of struggle.

Yeah, the struggle goes on.

Back to top of page.

Class

Struggle in the ‘New Economy’

You might have noticed if you’ve

read any of the bosses’ own publications (The Economist, Financial Times,

Business Week etc) that they are pushing the idea of a ‘New Economy’. An

economy based on the latest technology and IT, which has somehow overcome all

the contradictions of the ‘old economy’ and developed a fundamentally

harmonious basis; workers and bosses co-operating for the common good, the end

of workplace struggle.

| It’s the same self-serving

myth the bosses have always dished out when they want to make changes that

benefit them and harm us, right from the start of the Industrial

Revolution. Marx said 150 years ago that "It would be possible to

write a whole history of the inventions made since 1830 for the sole

purpose of providing capital with weapons against working-class

revolt", which is essentially what is happening today. The bosses are

trying to use work-place technology against us, whilst simultaneously

claiming it’s for our benefit. A look at what is actually happening in

the ‘new economy’ will dispel some of these myths. You have to look at

call-centres and similar workplaces and the production and assembly plants

that make the components for this new technology, not just information

workers or high-paid software designers.

The first thing to emphasise is that the

development of the New Economy is deliberate. It is the logical

result of mostly US state-funded development programs that explicitly

sought to create a pro-management environment through the use of

technology. The early electronic plants in the 1950s were used as

laboratories for road-testing new management plans to deal with the

collective strength of what became known as "the mass worker" -

a workplace community that had gained strength from the sheer numbers of

people concentrated in one plant. The concept of ‘team-management’

grew from this experiment and was exported to other industries most

notably the Detroit car factories and steel industries.

|

|

It’s not only the advertised product that the ‘new

economy’ is selling - it also sells plans to minimise worker resistance and

new ways of making us work harder for longer for less pay whilst watching us

every second. We should keep a very careful eye on what is happening in the ‘new

economy’ as it may very well be happening close to home before too long - as

the spread of just-in-time production, toyotism, self-management, work circles

and other management ploys have demonstrated. So how have workers been

responding to all this?

Worker Resistance

Despite the myths of a peaceful workplace there have been

numerous examples of class struggle taking place in the hi-tech sector -

practically from its origins. There’s a number of struggles that seem to be of

particular significance because of the areas in which they took place, how they

were organised, and the opportunities for spreading struggle among other parts

of the working. The 1993 strike by workers at the Versatronex circuit board

assembly plant in Sunnyvale, Silicon Valley was of great significance as it was

the first to take place among production workers (mainly female Mexican

immigrants) who are the basis of the ‘new economy’ but who remain hidden

behind the scenes in favour of stories about dot-com entrepreneurs. These

workers were employed in a sweat-shop: forced to work damagingly long hours,

with the usual problems that this causes in the family, at very high line

speeds, in unhealthy conditions with no medical plan and with very little pay or

job security. This is life at the most basic of levels of the ‘new economy’

- looks very much like life in thee ‘old economy’ doesn’t it? No stock

options here! The workers eventually struck and managed to spread the struggle

to other factories in Silicon Valley and to other immigrant workers in unskilled

jobs, janitors in these hi-tech factories being a prime example. The reality of

conditions in the ‘new economy’ met with a worker response straight out of

the old days of class struggle, of the boss and the worker having nothing in

common. The work conditions allowed the workers to socialise and talk of their

problems together and then come up with collective solutions. There was

recognition of the common problems felt by the women and the social solidarity

to do something about them. This contrasts with the better paid end of the

hi-tech sector where one of the most common complaints is the social isolation

felt by workers who no longer have to turn up at a definite place for a definite

time and who consequently feel they have to battle the boss alone or even that

there is no point in struggling at all.

Microserfs

Moving up the scale (so to speak) we have the programmers -

the people satirised as ‘micro serfs’ in Douglas Coupland’s novel of the

same name. A recent study by the University of California made the claim that

these jobs are the modern equivalent of the 19th Century factory. These workers

are a clear example of how the bosses myths of "modern flexible working,

untied by geographical office boundaries, able to work on their own initiative

and offered stock options in their firms." has been used against the

workforce. The reality is that these people are often forced into working 16

hours a day to meet deadlines (in some states overtime legislation has been

abolished), and are forced to constantly update their skills (not paid for by

the company) in order to stay in work. Resentment came to a head in the last few

years with the bursting of the dot.com bubble, the transfer of jobs to ‘developing’

countries and the mass immigration of IT workers prepared to work for lower

wages from those same countries. But "when the economic crisis hit, they

found themselves with few collective guarantees, they were cast to their

individual fates". There have now been a number of initiatives by these

workers to form some form of collective organisation - trade unions or

interest-based associations - to defend their interests and the lessons of

social solidarity that the Versatronex workers learned are now being taken up by

other sections of the ‘new economy’. However much of this still aims to

protect individual careers rather then improve conditions for workers as a

whole. One thing that this group has become aware of is that it has unique

skills which management takes for granted - assuming that people can be easily

replaced – but which they can use when deadlines loom. It’s a fact that is

increasingly being used to gain concessions; these workers have not yet had

their skills appropriated by the bosses. Whether this leads to 19th

Century-style craft unions and guild organisations or whether they are going to

recognise that their disputes are part of a wider network of struggles is going

to be a key question over the coming years.

Telecommunications

Call centres stand somewhere in the middle ground: neither

production work nor designing and developing original plans, they are (along

with data-entry clerks and similar) stuck in boring repetitive factory-like jobs

but their tools are no longer the lathe but the pc. They are probably the most

monitored workforce going, with constant intrusive supervision, almost every

single task broken down into timed actions and compulsory overtime.

Unsurprisingly this has led to well above average workforce turnover, sometimes

a high as 80%, as stress levels become just too high. August 2000 saw 87,000

telecommunications workers strike against Verizon Communications in the US over

forced overtime, job stress and job security. Forced overtime was the key issue:

in some states management can force people to work 15 hours a week overtime,

more in certain months, while another (New Jersey) has no limits on the

amount of overtime that can be forced on workers. As one striking technician put

it, "Management can come up to you as you are getting ready to leave and

require you to work another two hours, or before your day off they can require

you to work four hours of it." This is now the norm throughout the industry

- not an exceptional case at all. Other complaints were the speed of work

and the supervision - a striker wrote : "For every call that comes

in we have to 'assume the sale.' If we do not try to find a need and sell the

customer a new service then we are disciplined. Depending on the supervisor, you

could get a suspension. All of this and completing the repair or customer

service order has to be done within specified time constraints. For a customer

repair the calls have to be down to 300 seconds. Five seconds over and we are

reprimanded… Mostly everyone in the business office is on Prozac.

Many people are also out on sick leave due to the stress. I transferred out

after two years. On Sunday nights I couldn't sleep because I was thinking about

going back to work on Monday. That job was hell."

The strike which seemed so solid after two weeks out was

brought to a halt by another throwback from the ‘old economy’ - a union sell

out. The Communication Workers of America (CWA) split the workforce and all but

ran a strike-breaking operation in areas where they met with determined

opposition, imposing a deal that actually made the workers job even more

stressful. The lesson in the ‘new economy’ remains the same as in the old:

don’t trust union bureaucrats, rely on your own autonomous strength and

solidarity in collective action. In the last years or so there have been strikes

in call-centres all over the world (and a possibly quite large one looming at

BT) as workers come to realise that many companies are now almost totally

reliant on these modern day sweatshops. They are in fact a weakness that can be

exploited, a point where capital is particularly vulnerable.

Common to all the above sectors is stress. A recent TUC study

has shown that: "Workers with stressful jobs are more than twice as likely

to die from heart disease. An individuals mental health deteriorates when a

change in workload results in higher demands, less control and reduced support.

Poor management planning and organisation can lead to heart disease. Working for

unreasonable and unfair bosses leads to dangerously high blood pressure. Workers

are smoking, drinking and ‘slobbing out’ to deal with workplace stress.

Long-term work-related stress is worse for the heart than aging 30 years or

gaining 40lbs in weight." This is the ‘new economy’, eating up the

working class just as surely as did the ‘old economy’

The boss talk of class harmony and co-operation is being used

to deny all of this. But the fact is that a society that is organised around the

capital-labour relation can never escape class struggle, can never escape from

bosses vs workers. It may be old but its still true:

"The working class and the employing class have nothing

in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among

millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class,

have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the

workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of

production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth."

Back to top of page.

Anarchist

Federation (Ireland) and Anarcho-Syndicalist Federation

Statement on Trade Unionism and Industrial Organisation

The Role of

Trade Unions

The Anarcho-Syndicalist Federation (ASF)

and Anarchist Federation (AF), as organisations of class-struggle anarchists,

agree that trade unions cannot be used, in the long term, as vehicles of

revolutionary activity in Ireland.

Here, as elsewhere, trade unions are

top-down organisations of bureaucrats and workers where those at the top (the

bureaucrats and trade union elite) stifle the hopes of those at the bottom (the

workers) and impede their natural desire for an improvement in working

conditions. This elite is nothing but a management board of full-time, permanent

officials motivated by self-interest alone, with even less interest in rocking

the industrial boat. Trade union officialdom will not, for example, involve

workers in long-term strike action that would interrupt the flow of precious

union dues. In short, trade unions are not controlled by their members; it is

they who control. The fact that trade unions like SIPTU have scrapped notions of

one-man, one vote, and will not even countenance changes in the ways they are

organised, is testament to the stranglehold union bureaucracies have over

workers.

As capitalism is an exploitative

system where workers produce the wealth, but do not receive it, trade unions, by

promoting collective bargaining, are also promoting and legitimising

exploitation. In recent times, the ‘social partnership’ entered into by

trade union leaders and bosses has made this even more self-evident, while

Public Private Partnerships (PPP) and Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) are

paving the way for private investment in the public sector. In the meantime,

trade unions are overseeing the run down of our public services which will be

ultimately paid for by an increase in our rates and by the introduction of water

charges in the north.

However, the AF and ASF do not

believe that its members should not join trade unions. While we realise that

they will never be able to step onto the revolutionary stage, we also

acknowledge the benefits to be gained by union membership in the short term.

Trade unions are places where workers can gather together, and where progressive

ideas can be discussed. Trade unions can also offer better Health and Safety

conditions, legal protection, and support over minor quibbles with management.

Shop-Stewards and Union Reps

The ASF and AF accept that in some

cases - for example in militant workplaces - it may be worthwhile for its

members to become shop-stewards or union reps. (Having said this, in periods of

industrial calm, there is nothing to bar our members becoming shop-stewards if

they feel that by doing so they can make a contribution to the struggle against

the boss class.) An AF or ASF member who becomes a shop-steward will do so as a

delegate, and not as a mouthpiece for management. The role of the

shop-steward/union rep will be seen not as a means to advance the interests of

our organisations specifically, but as an opportunity to advance anarchist ideas

generally. However, the ASF and AF realise that becoming a shop-steward/union

rep is a lesser tactic in the ongoing struggle against capital, and would argue

more for autonomous working class organisation (see below).

Rank-and-Filism

The AF and ASF are supportive of

rank-and-file initiatives, while remaining aware of how these initiatives are

often used as Leninist fronts whose sole object is to force through a particular

party line. Rank-and-filism can provide us with the experience and confidence we

need to become better militants and can help us in our fight against bosses.

Ultimately though, it will never be able, by itself, to break the trade unions’

tie to so-called Labour parties, old or new, to radicalise enough workers to

affect any major change to how trade unions function now or will function in the

future. We agree that trade unions cannot be reformed, or democratised from